CHICAGO — The stakes were high as tens of thousands of Democrats descended this week on Chicago for their nominating convention, and law enforcement braced for potentially violent protests outside the United Center.

Comparisons were drawn to the 1968 Chicago convention, when national unrest during the civil rights movement and over the Vietnam War sowed an atmosphere of violence and chaos.

The 2024 Democratic National Convention unfolded quite differently, however, with both protests and policing bearing little resemblance to the turmoil of 56 years ago.

“If the 1968 convention went down as the example of police brutality, then the 2024 convention will go down as the example of constitutional policing,” Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson told reporters Friday.

Chicago Police Department officers were trained to deploy a disciplined and patient approach that focused on protecting free speech and allowing people to lawfully protest, a department official said. In the handful of instances in which tensions between police and protesters escalated, police zeroed in on a small number of people who attacked officers or disregarded dispersal orders.

“The department trained more than a year for this,” a Chicago Police Department official who was not authorized to speak publicly told NBC News.

That training “focused on de-escalation,” according to the official, who added there’s an appetite in the department for training that would have a “transformative” effect.

“We are trying to get away from the old image of the Chicago Police Department,” the official said.

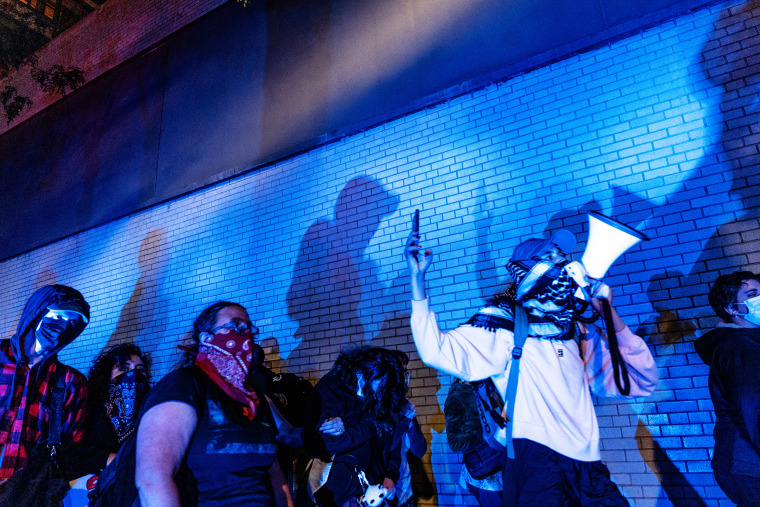

Demonstrations held Sunday through Thursday remained mostly peaceful, with one glaring exception: A protest on Tuesday organized by Behind Enemy Lines and Samidoun — an organization banned in Israel and Germany that praised Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack — quickly turned violent. More than 50 people were arrested and at least four people suffered minor injuries during scuffles.

In all, 74 people were arrested between Monday and Thursday, according to Chicago police. The department estimated protest attendee numbers were in the low thousands, far below the tens of thousands organizers had predicted.

On Sunday, several hundred people gathered in downtown Chicago for a protest organized by Bodies Outside of Unjust Laws, a group that describes itself as a coalition of leftist organizations advocating for a broad list of topics, including reproductive justice and an end to the war in Gaza.

On Monday, the Coalition to March on the DNC held its main rally. Organizers said they were expecting 20,000 to show up and maintained that some 15,000 did, but police put the number closer to between 4,000 and 6,000.

It remained mostly peaceful until demonstrators arrived within sight of the convention. At that point, a breakaway group of protesters climbed onto perimeter fencing and began tearing it down. People attempted to pour into the barricaded area as police in riot gear largely stood by ordering them to disperse.

Officers quickly restored the fencing after consulting with Secret Service officials, Police Superintendent Larry Snelling told reporters the next day. During the briefing, he praised both police officers for showing restraint and the majority of protesters who “just wanted to make their voices heard.”

“We put on display the preparation and training we’ve been engaged in for over a year now,” he said.

But just a few hours later, the mood soured when a protest outside the Israeli Consulate turned violent.

Pro-Palestinian groups repeatedly ignored dispersal orders, charging into police lines, throwing signs and water bottles at officers in riot gear, and leading several hundred demonstrators on an improvised path through the streets of downtown Chicago after police tried to block them.

Michael Boyte, co-founder of Behind Enemy Lines, said the organizing groups didn’t set out to clash with police that day and dismissed the notion that law enforcement used restraint when responding to demonstrations.

“From the moment we got there, there was an intimidating show of force on behalf of the CPD, who made it clear that they were not going to permit any kind of free expression happening at the consulate,” he said. “We think it’s a legal right and a moral obligation to protest the genocide.”

The rest of the week, several thousand protesters took to the streets each evening in largely peaceful demonstrations. A handful of protesters holding an overnight sit-in Wednesday night ended without incident.

While the number of protesters throughout the week didn’t live up to organizers’ estimates, they still arrived in far greater numbers than they had during last month’s Republican National Convention in Milwaukee.

“The story is that the police were not the story,” said Chuck Wexler, the executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a policing think tank in Washington, D.C.

Ed Obayashi, a former police officer who consults with multiple police departments throughout California on use-of-force issues, said that, overall, Chicago police did a good job policing the convention and that protests lacked the numbers or intensity to significantly disrupt events.

“Their presence, to a large degree, was a deterrent to violence. It was clear and authoritative,” he said, referring to Chicago police.

But Brad Thomson, a volunteer attorney with the National Lawyers Guild of Chicago who monitored protests all week, said the “massive” police response was “just completely disproportionate to the size of the crowd.”

Obayashi, however, noted that the small number of protesters coupled with the minute number who were seeking to be disruptive failed to “push” the buttons of law enforcement. Notable, too, was the presence of Superintendent Snelling, who appeared on the front lines alongside police officers throughout the week.

At times he personally stepped in to handle a specific policing matter. On Wednesday, for example, after a woman threw a water bottle at an officer and was apprehended, police officials said Snelling personally intervened so that she was released and not booked.

“He is leading from the front, instead of behind a desk, he is able to control his people,” said Terence Monahan, a former top official with the New York Police Department. “He sees firsthand what’s going on. He can direct the actions that need to be taken.”

Several protesters agreed that police exercised restraint and discipline repeatedly, but feared it was just a temporary act that will disappear after the spotlight fades from Chicago.

“I am a bit cynical,” said Chicago resident Eduardo Castelao. “The city commanded officers to stay calm, but it seems to me like they’ll be back to their usual stuff as soon as the convention is over.”

Nick Sous, an organizer with the U.S. Palestinian Community Network who helped organize the Coalition to March on the DNC, said that, while he was “pleased” the police “did their job,” he would have preferred they did not come at all.

“I don’t think we needed the police this week,” said Sous, a Chicago resident. “Our marshals protected us more than adequately,” he said.