BBC

BBCIn the next 24 hours and then over the following fortnight up until the Spring Statement, the government is going to talk a lot about a broken welfare system that is failing the people who use it, the economy and taxpayers.

Taking a tough call on fixing it goes against the instincts of much of the Labour Party and has already sparked an internal backlash that could rise to ministerial level, as well as protests.

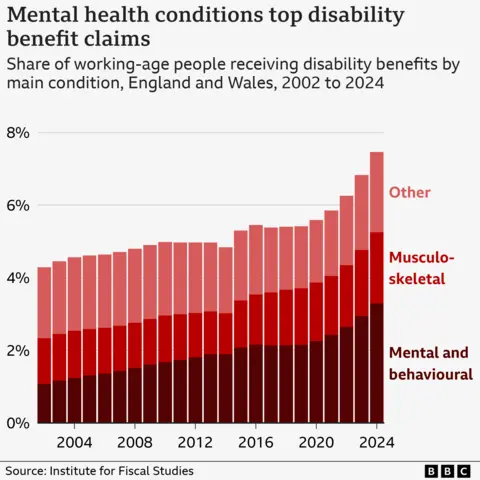

The Government is making two key related judgments: The first is that the country cannot afford to sustain recent ballooning increases in the health-related benefit bill and caseload, in particular for mental illness.

At the same time, it will argue that a job is the best medicine.

Underlying this is an assumption that a health-related benefits system that was built-up to deal with industrial injuries can’t apply to the post-pandemic service economy workforce.

The net result is likely to be significant changes to Personal Independence Payments, aiming to reduce eligibility for the highest levels of payments, especially among those of working age with mental illness.

In addition, there will be a levelling of the generosity of the health component of Universal Credit. This will save billions of pounds, and about a billion of that will be reinvested in trying to help get those capable of part-time work some help for a partial return.

Mapping welfare trends

The Department of Work and Pensions is rolling in real time data. “Cluster analysis maps” reveal to ministers exactly who is claiming out of work benefits and where they are.

As the numbers continue to increase, the data is being cut by sector, postcode, age and type of illness. Every pattern is being analysed.

The idea was that the data would firstly offer the government insight into how it could make billions of pounds of cuts to a rapidly growing bill in order to help the Chancellor meet her self-imposed government borrowing rules.

Secondly, it was meant to point to more fundamental reforms to welfare, also designed to temper the same ballooning rise in the costs of dealing with ill health among the working population.

The data has thrown up answers.

That poor mental health is driving the rise in claimants is clear. To a lesser extent, so too is the role that raising the state pension has played, with many thousands who would previously have been retired now claiming health-related benefits.

But it has also thrown up a major question too: does cutting welfare to incentivise people to work more hours in fact do the opposite – nudging them out of the workforce altogether and ultimately increasing the benefit bill?

If this is the case – and it is by no means a universally accepted interpretation of what has happened – then the question is whether further cuts could in fact increase the numbers claiming? And should Labour instead invest in getting people back into work?

Growing sickness

When I visited a job centre in Birmingham alongside the Work & Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall in the Autumn, I was taken aback by how the work coaches were talking as much about health as about work.

“There’s a lot of mental health, depression and anxiety,” Qam told me.

GPs have reported that their surgery time is dominated by trying to work out whether their patients are “fit for work”. Roughly 11 million fit notes are issued every year in England alone, with 93% assessing the patient as “not fit for work”. That has doubled over a decade. In the latest quarter, 44% were for 5 weeks or more absence.

From that pool of growing in-work sickness, a significant proportion ends up on some form of incapacity benefits. The Treasury’s bill for health and disability benefits, which was £28bn in the year before the pandemic, is now £52bn a year. It is forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to hit £70bn by the end of the decade.

The pure financial aim here is to “bend the curve” down to nearer £60bn in that period. This means restricting both the generosity and eligibility of some – or all of such – payments. It could require a wholesale cash freeze so that benefits do not rise with inflation, for example, or the abolition of entire categories of recipients.

“Deaths of despair”

An Institute for Fiscal Studies report published last week showed that wider measures of mental ill health have rocketed since the pandemic. Between 2002 and 2024, the number of 16-64-year-olds claiming disability benefits for mental or behavioural health conditions increased from 360,000 to 1.28m.

Every day in 2023 there were 10 extra “deaths of despair” (defined as deaths from alcohol, drugs or suicide) in England and Wales than the average between 2015 and 2019. Average sickness absence rates across the whole economy remained structurally higher than pre-pandemic.

Of particular concern is how this affects young people. In a recent report DWP adviser Professor Paul Gregg points to the “incredibly low” chances of sustained returns to the workforce once a person has been on incapacity benefits for two years.

About two fifths of new incapacity benefit claimants under 25 came directly from education. The latest DWP analysis shows these trends are now closely related to broader socio-economic vulnerabilities such as limited education and also with precarious sectors such as retail and hospitality.

The question that remains is whether so many people really are more sick – and what role (if any) is played by the reduction in stigma around mental health.

But then there is the question of how to address it.

Overly binary

Another major factor is that rise in the state pension age, which the DWP calculates, resulted in 89,000 older workers instead claiming health-related benefits. However, the sharp increase in claimants of such benefits since the pandemic is not only attributable to ageing populations or increasing mental health diagnoses.

Research suggests there are significant systemic and policy-driven causes. At its heart the problem is perceived to be that the current welfare structure has become overly binary, failing to accommodate a growing demographic who should be able to do at least a bit of work.

This rigidity – what ministers refer to as a “hard boundary” – inadvertently pushes individuals towards declaring complete unfitness for work, and can lead to total dependence on welfare, particularly Universal Credit Health (UC Health), rather than facilitating a gradual transition back into employment.

PA Media

PA MediaThis has been bad for the economy, for employers, terrible for the public finances, and deeply concerning for the career prospects of individuals.

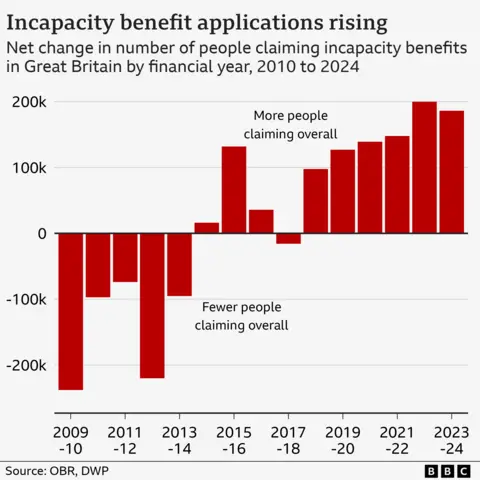

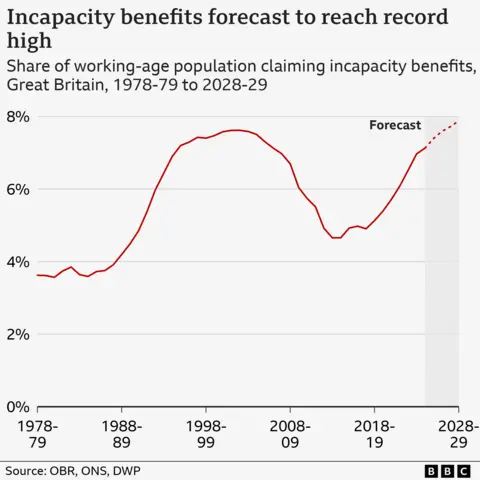

History helps here. Health related benefits are often a disguised form of unemployment. The caseload for incapacity benefits (which include not just UC Health but previous incarnations) since the 1970s shows the UK heading for a record of one in 12 adults of working age in receipt.

But this is not the first such build-up. It happened in the late 1980s when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister, and it was reversed in the early 2000s under New Labour.

The launch in 1986 of Restart Programme, a forerunner to JobSeekers Allowance modelled on Ronald Reagan’s policies in the US, helped return many claimants to the workforce but also pushed a staggering number into incapacity claims.

Over the decade and a half of this policy, there was a 1.6 million increase in people in receipt of the benefit. But at the time this migration from claimant unemployment into incapacity was apparently a deliberate strategy, as it helped deal with headlines about “three million unemployed”.

A middle ground

The Government has not yet published its analysis on the jobs market, but Professor Gregg’s early thinking was made clear in a report for the Health Foundation. He argued that, historically, the welfare system responded effectively through a middle ground that allowed individuals to combine part-time work with partial welfare benefits. He puts this down to reforms introduced in the early 2000s, such as tax credits.

This is essentially the crystallisation of Iain Duncan Smith’s critique of then chancellor George Osborne’s welfare cuts of 2016. He told me at the time that they were “deeply unfair” on working people and the vision of a proper welfare-to-work scheme “could not be repeatedly salami-sliced”.

PA Media

PA MediaSome argue that those reforms created a situation where individuals, unable to sustain full-time work, gravitate towards more generous health-based welfare program.

Crucially, claims began to rise in 2018. At the DWP ministers have tried to research the reasons behind the increase in caseload – and found that about a third of the increase can be explained as the predictable consequence of policy or of demographics.

Prevention rather than cure

With an ongoing flow of new claimants arriving in the system (nearly half a million in the last financial year) the onus is now on finding a prevention rather than a cure.

And this is where it becomes tricky – one suggestion involves eliminating the current welfare trap by reintroducing intermediate support for part-time work. However, that requires extra funding, aa well as a way of providing more personalised job searches and better mental health support.

Reuters

ReutersAnother option is passing responsibilities to employers. In the Netherlands, employers bear significant responsibilities and financial costs if they fail to adequately support employees facing health challenges. In the early 2000s, the Dutch also had very high levels of incapacity but they now report employment rates of 83%.

The structure of the jobs market in the UK makes that challenging to replicate – for example there are more insecure zero hours contracts.

And given that businesses feel under pressure from National Insurance rises and a slow economy, could they really be cajoled into helping?

Faster cuts

The questions arising from the data will matter for the economy, for the public finances, our health, and young people’s careers and livelihoods, at a time of considerable change.

Fundamentally, it is a question of what the benefit system is for, at a time when illness is being redefined, and when the trends are, frankly, scary.

Then there is the question of whether the public wants to pay even higher taxes in the hope of delivering long-term gain. Welfare-to-work programs can pay for themselves eventually, but the Government feels it needs to book faster cuts.

That’s because all of this is in the context of what “fiscal headroom” the government did have against the Chancellor’s self-imposed borrowing targets being wiped out since the Trump shock to the world economy, the Budget and the announcements of extra European defence spending.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockBut government insiders are at pains to argue that the primary motivation for any cuts is not regaining the extra room for manoeuvre. “We don’t need the OBR to tell us that we need to fix welfare to get people back to work. We don’t need the OBR to tell us we need to make the NHS more productive. And we don’t need the OBR to tell us that the taxpayer should be getting more value for money,” a source told me.

“Headroom or no headroom the Chancellor is determined to push through the change we need to make Britain more secure and prosperous.”

Ultimately, the economic imperative is clear – to bring a cohort of young people suffering a combination of mental ill health and joblessness back into work.

And the government believes there is no way of doing this without, at least at first, hurting the incomes of ill people. There is going to be quite the backlash from disability charities, and in turn from backbench Labour MPs.

That’s why it’s no exaggeration to say this month’s explosive row about welfare will come to define this Government.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.