Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

As a child, Alexandra Walker endured years of what she describes as emotional abuse by her father. By the time she reached her thirties, her father’s worsening alcohol dependency only put further strain on their already fractured relationship. Alexandra decided to cut ties with him during the Easter period in 2022. Just over a year later, Alexandra received a call from her father’s neighbour informing her that he had not been seen for several weeks; his lawn was overgrown and his post was piling up. He was then found in his home, having been dead for about a month.

From this point, Alexandra experienced every emotion imaginable. There was guilt. Shame. Sadness. “I had always been nervous about my father’s death because he had cut ties with almost everyone in his life,” Alexandra tells me. “It was shocking to deal with the reality of the fact that he died alone. I had a mixture of anger about the whole thing. And disbelief, and shock. And if I’m being really honest, there was also a sense of relief, because I couldn’t see any good end to his situation. I just knew that it was only going to get worse because he had isolated himself.”

Addressing the loss of a family member with whom you had a complex relationship is never easy, nor straightforward. This is something that Mariah Carey is likely grappling with this week, after she announced that her mother, Patricia, and her estranged sister, Alison, died on the same day. The causes of their deaths remain unknown.

In her 2020 memoir, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, the singer-songwriter described her relationship with her mother as one characterised by “betrayal and beauty”, “love and abandonment”, and filled with a combination of “pride, pain, shame, gratitude, jealousy, admiration and disappointment”. She continued: “Like many aspects of my life, my journey with my mother has been full of contradictions and competing realities. It’s never been only black-and-white – it’s been a whole rainbow of emotions.”

She also wrote that her therapist encouraged her to “rename and reframe” her family and her relationships with them. “My mother became Pat to me, Morgan my ex-brother and Alison my ex-sister,” she wrote. “I had to stop expecting them to one day miraculously become the mommy, big brother and big sister I fantasised about.”

Carey also wrote of her strained relationship with Alison, writing that her sister was “brilliant and broken” and had experienced things that had “damaged and derailed her girlhood”. She alleged that her sister “drugged me with Valium, offered me a pinky nail full of cocaine, inflicted me with third-degree burns, and tried to sell me out to a pimp”. She later came to accept that it was “emotionally and physically safer” to withdraw contact from her sister instead of continuing a relationship.

There could be a whole bunch of people who are pretending to forget all the bad stuff that happened. It can be kind of gaslighting. And that can be very isolating for people

Sarah Lee, psychotherapist

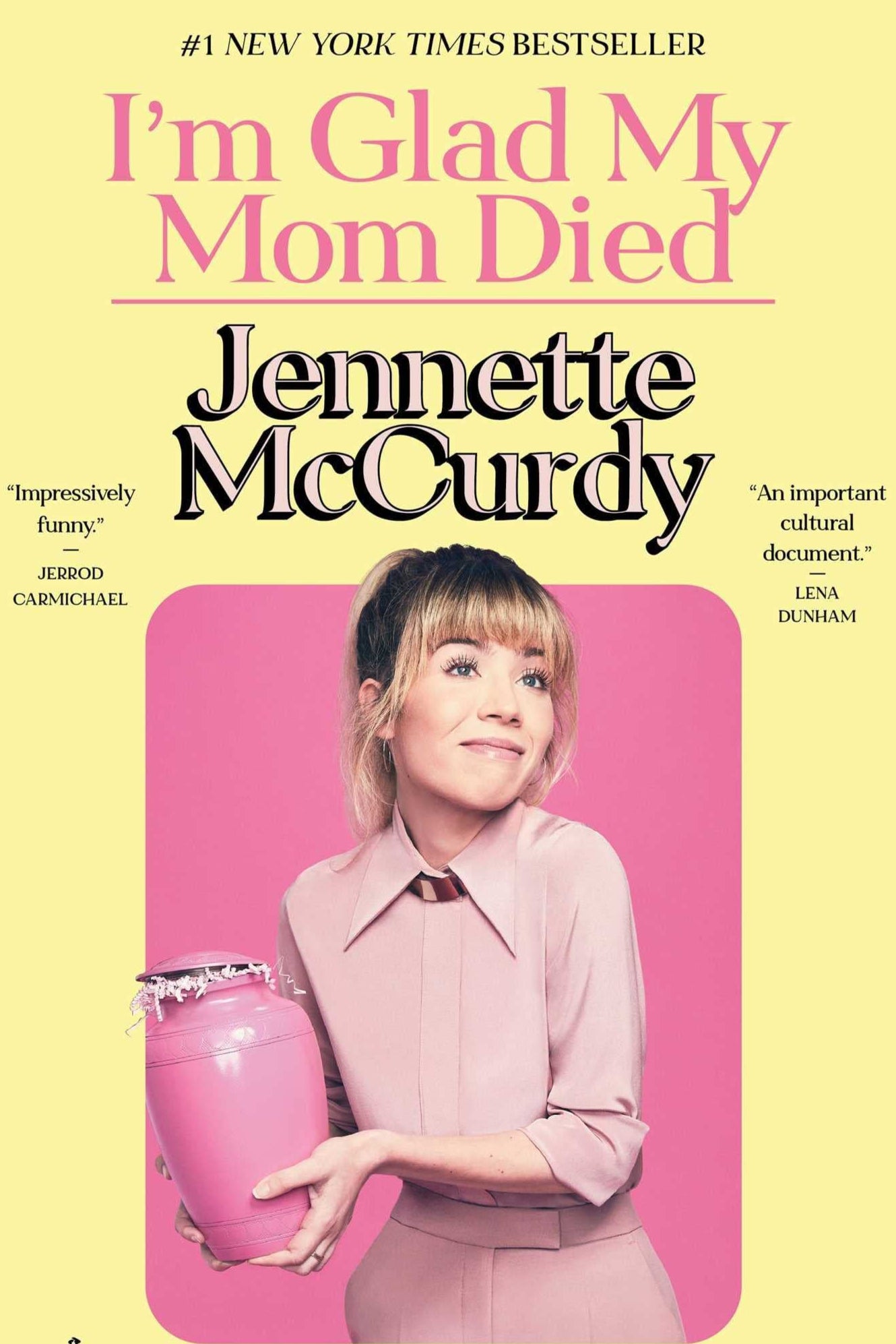

Carey’s complicated state of grief was also articulated by former child star Jennette McCurdy in her own memoir, 2022’s bestselling I’m Glad My Mom Died. It recounts her relationship with her mother, Debra, who McCurdy says was abusive and invasively controlled every aspect of her life, from her friendships down to her body hair. McCurdy was relieved when her mother died and the abuse finally ended, but that also didn’t mean that she didn’t miss her, or grieve for her. “I used to really have a complicated relationship with missing her; I’d miss her, then I’d feel angry and that she doesn’t deserve for me to miss her,” McCurdy told The Guardian when promoting her book. “[My mother] abused me, how do I still have love for this person? It was a deeply confused form of grief.”

Grief has many layers. But with the added context of a fractured – or abusive – relationship, the experience is sometimes much more distressing than losing someone you were on good terms with. Sarah Lee, a UKCP psychotherapist who works with childhood trauma survivors in Manchester, tells me that the experience of losing a family member who harmed you can be isolating. Society tends to instruct us that there’s only one way to speak about the deceased – that we have to be respectful, solemn and sad. Shades of grey aren’t enormously encouraged.

During our conversation, Lee describes a hypothetical scenario in which an adult attends the funeral of their abusive parent, and watches their life being celebrated in a wholly positive light. “Maybe that person is really sad at the funeral because everyone’s talking about how great their parent was,” she says. “They go home and they start thinking, well, hang on a minute. ‘What about all the times they left me at home on my own to go out drinking? Or they told me that they hated me? Or that my life was completely pointless?’ And then they get angry.” Lee tells me that this is one example of the emotional “jumping around” that comes with this type of grieving process.

Lee says that self-blame and self-loathing might accompany these emotions. While there is no one way to grieve, beliefs like “Don’t speak ill of the dead” are often widely adhered to – and veering away from the norm might raise some eyebrows. “There’s a potential to feel triggered by the fact that you’re not doing ‘grief properly’ or feeling judged by other people,” says Lee. Some people might try to excuse the wrongs of the deceased person, or try to portray them in a more positive light, which can leave the affected family member(s) even more isolated. “In dysfunctional families, there’s a massive system of denial,” explains Lee. “There could be a whole bunch of people who are pretending to forget all the bad stuff that happened. It can be kind of gaslighting. And that can be very isolating for people.”

In Alexandra’s case, her father did not want a funeral, so she didn’t have to attend any events with the people who knew him after his death. Since then, she’s been keen to speak about her experience. She left her corporate job to re-train as a life coach and now helps other people through traumatic experiences. But she also felt that there was an expectation from others that she shouldn’t talk about her father’s flaws openly. “People always struggle with grief, but the people I know, in my friends and family, struggled even more than usual,” she explains. “There were some amazing family and friends who really did sit with me [and listen]. And I don’t blame those who couldn’t. It just made it a bit more lonely because a lot of people just couldn’t engage with it because it was too difficult. I think there’s a pressure to move on and not talk about it any more.”

Alexandra says that she believes in honouring her parents, but at the same time, there are some situations “where you know harm has been done”. “If we don’t raise awareness of emotional abuse, people won’t understand how damaging it is. But I think for some people it’s still ‘Oh, it’s just emotional abuse. It’s not that bad’. But if you look at the evidence, it has really long-lasting emotional and physical impacts on people.” Alexandra says that as a young adult, she developed a range of mental health issues, including OCD, anxiety and chronic insomnia, which, in hindsight, were linked to the ways she was forced to be hypervigilant around her father and his angry mood swings when she was a child.

There’s a saying that tells us grief “comes in waves”. For Alexandra, she mourned her relationship with her father when they became estranged in 2022. But his death brought up a second set of emotions. Lee calls these two experiences the “first and second grieving”, and it’s usually linked to the deaths of estranged family members. When two people first sever ties, there might be a level of acceptance. But when that person is gone, it makes the situation even more finite. “In some cases, even when there has been a lot of the first type of grieving, death is like the second trigger,” explains Lee. “When someone’s gone, you can’t hold out hope anymore that one day they’re going to wake up and regret how they’ve treated people.” In that sense, the second grieving is about “accepting that they’re not coming back”.

Lee adds that shame is often projected onto those who admit to feeling a sense of ease or relief when someone has died. “People will say to me, ‘I feel really bad but I’m not that sorry that they’re not here anymore’, or ‘I don’t think I would be sad when they die’,” Lee tells me. “They will ask: ‘Does that make me a terrible person?’ I say, ‘No, because you had a terrible relationship with that person. It actually makes a lot of sense that you’re feeling this way’. It’s hard to admit but it’s also very freeing to be able to say it.”

But she also says that experiencing these feelings doesn’t make you evil. It doesn’t make you ungrateful for the good bits of that relationship, either. “Whatever you’re feeling is fine,” she says. “It doesn’t make you a bad person.”

If you need help to cope with someone’s death, you can call the Cruse bereavement support helpline free on 0808 808 1677. There is also a free chat service available on the charity’s website at cruse.org.uk

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch. If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org to access online chat from the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you.