The proposal is more than two years in the making and won’t become final until at least 2026. Yet it is already facing stiff resistance. Employers in industries from agriculture to construction, tourism and oil and gas extraction have argued that it’s unnecessary and could hurt their competitiveness. It is likely to encounter major obstacles, including the near-certainty that it would be abandoned if Donald Trump were to win the presidency in November.

But if the rule takes effect, data analyzed by The Washington Post shows that it could be transformative for workers — especially in the South.

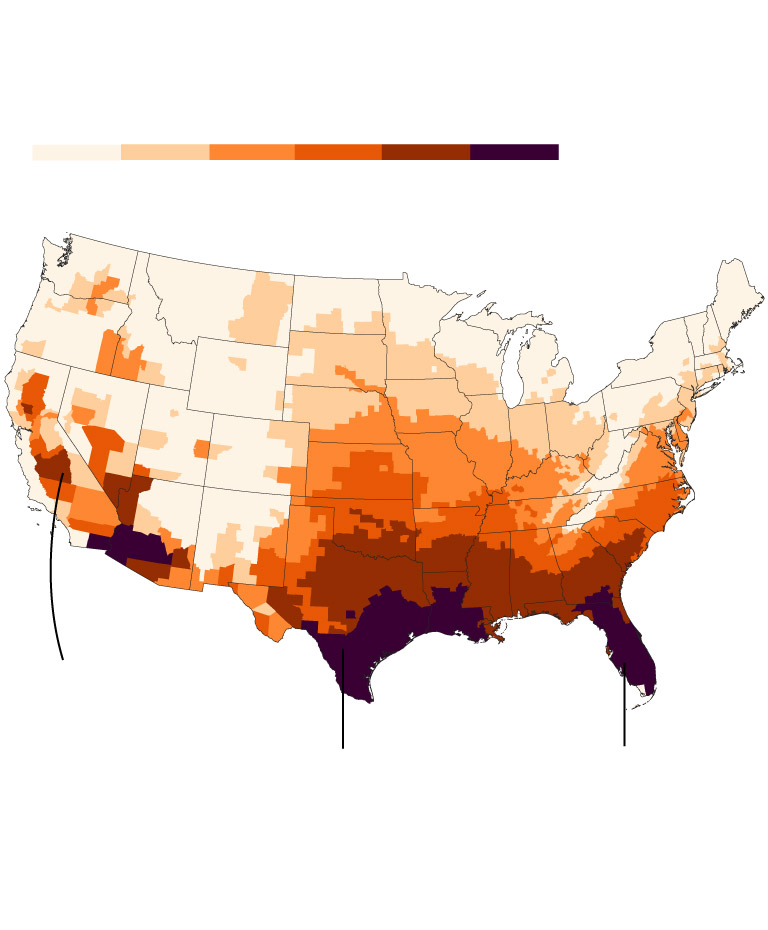

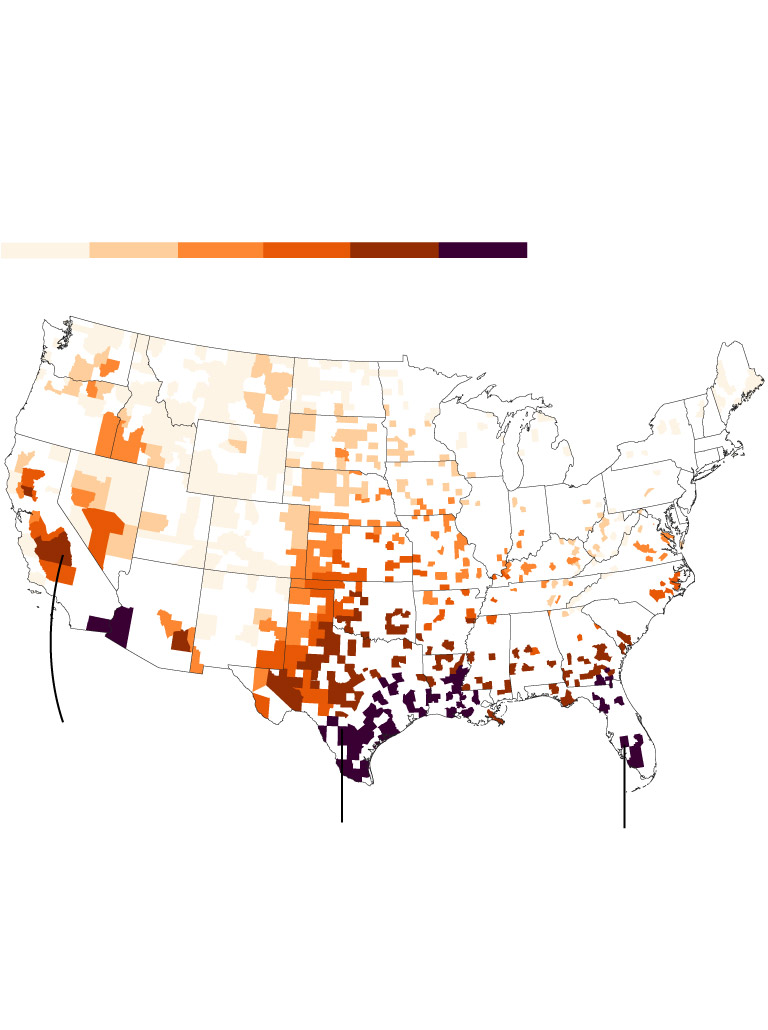

Where extreme heat is most prevalent in the lower 48

Annual days with maximum heat index

of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

104 heat days per year

DeSoto, Fla.

166 heat days per year

Frio County, Texas

159 heat days per year

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

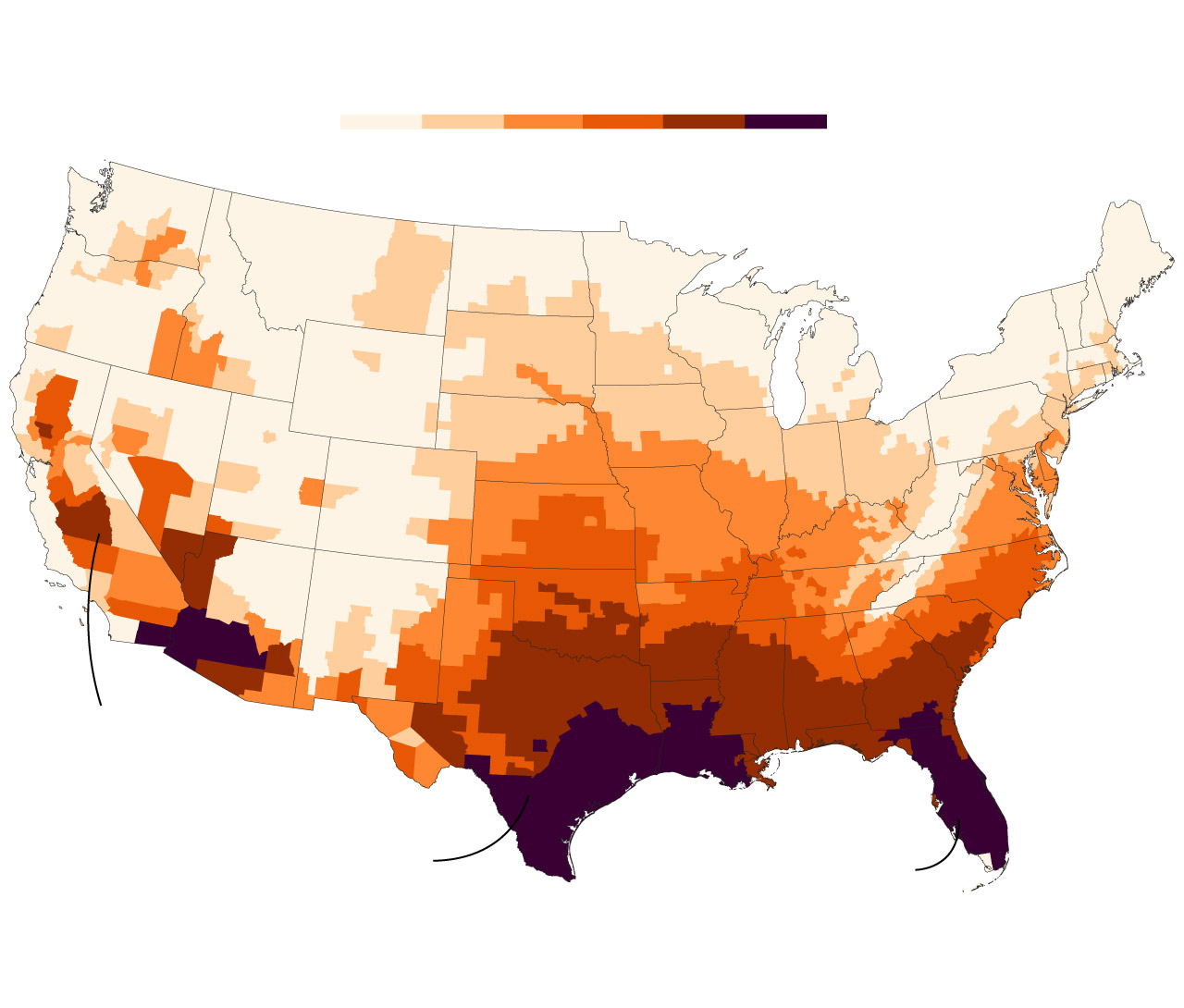

Where extreme heat is most prevalent in the lower 48

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

104 heat days per year

Frio County, Texas

159 heat days per year

DeSoto, Fla.

166 heat days per year

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

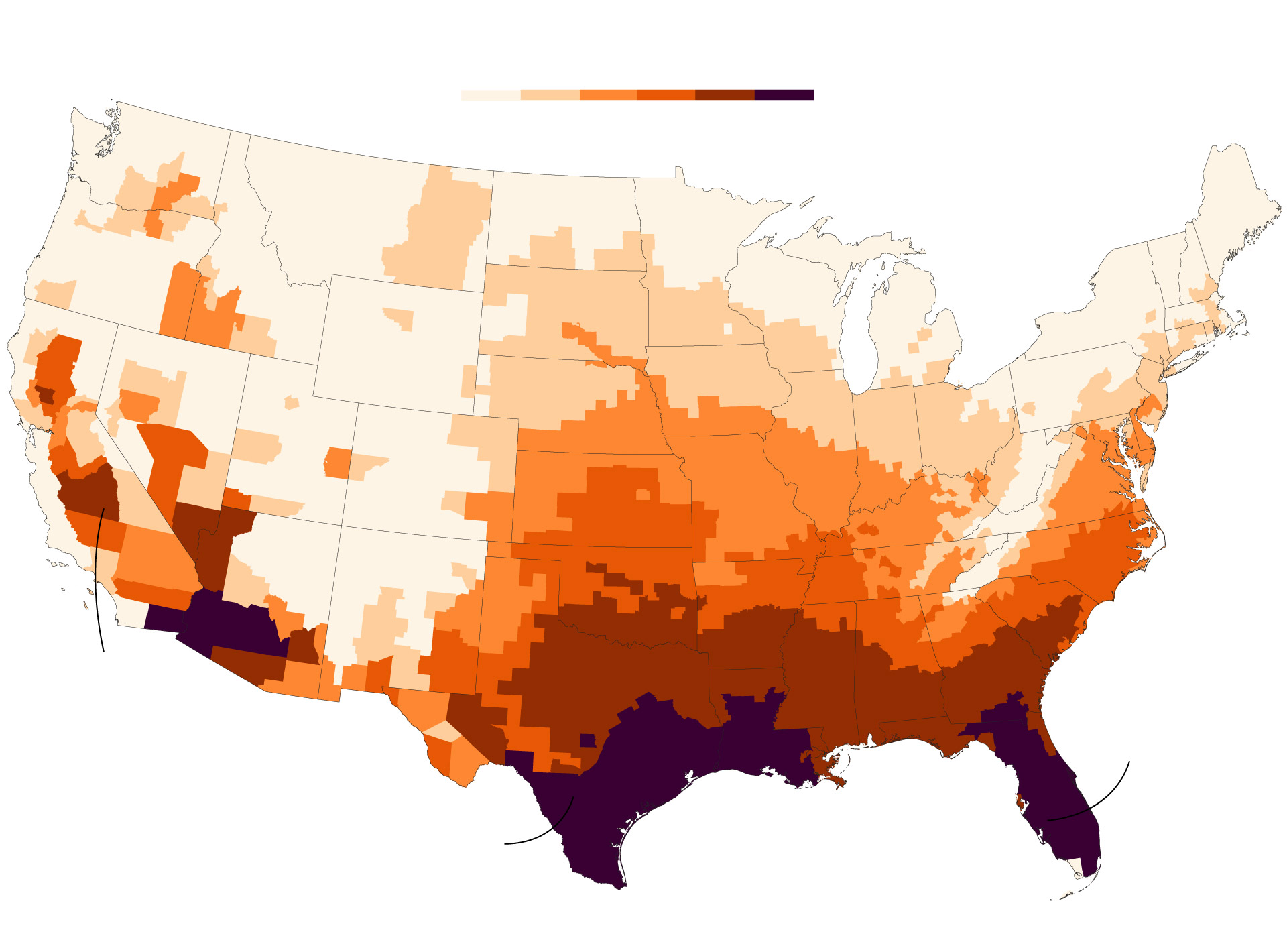

Where extreme heat is most prevalent in the lower 48

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

104 heat days per year

Frio County, Tex.

159 heat days per year

DeSoto County, Fla.

166 heat days per year

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

Where extreme heat is most prevalent in the lower 48

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

104 heat days per year

DeSoto County, Fla.

166 heat days per year

Frio County, Tex.

159 heat days per year

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

The region’s punishing heat and humidity have long been a workplace hazard. Although Texas and California accounted for a quarter of all heat-related workplace fatalities from 2000 to 2010, workers in Southern states face the most lethal threat when the size of worker populations is taken into account. Mississippi, Arkansas, Nevada, West Virginia, and South Carolina had the highest rates of heat-related deaths on the job during that period.

Southern states are highly dependent on agriculture and home-building — the two jobs where workers face the most risk from heat — and with low rates of union membership, working-class laborers have little power to demand protection. Factor in the effects of climate change — more-frequent heat waves and extreme temperatures — and the future of work in these states is increasingly dangerous.

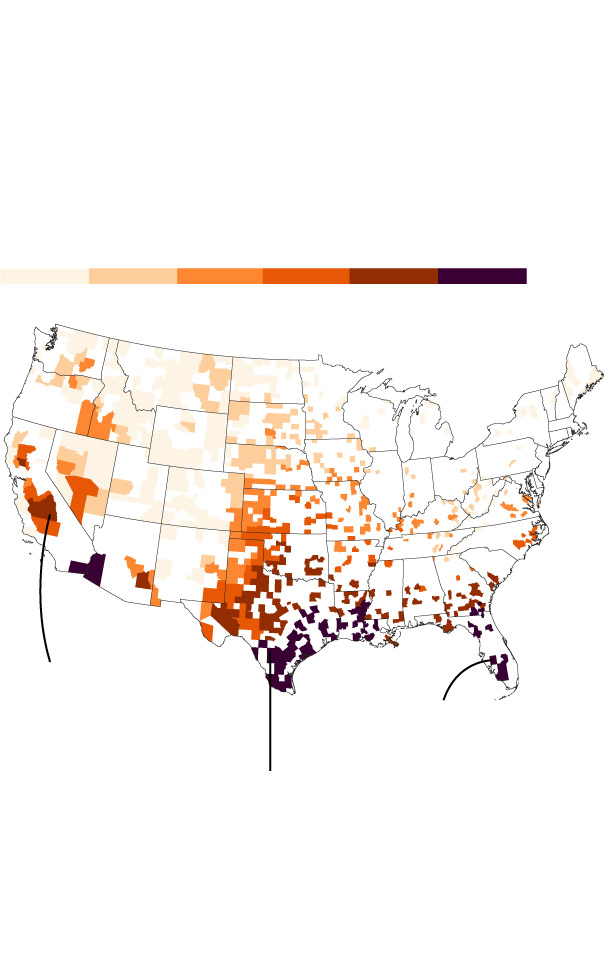

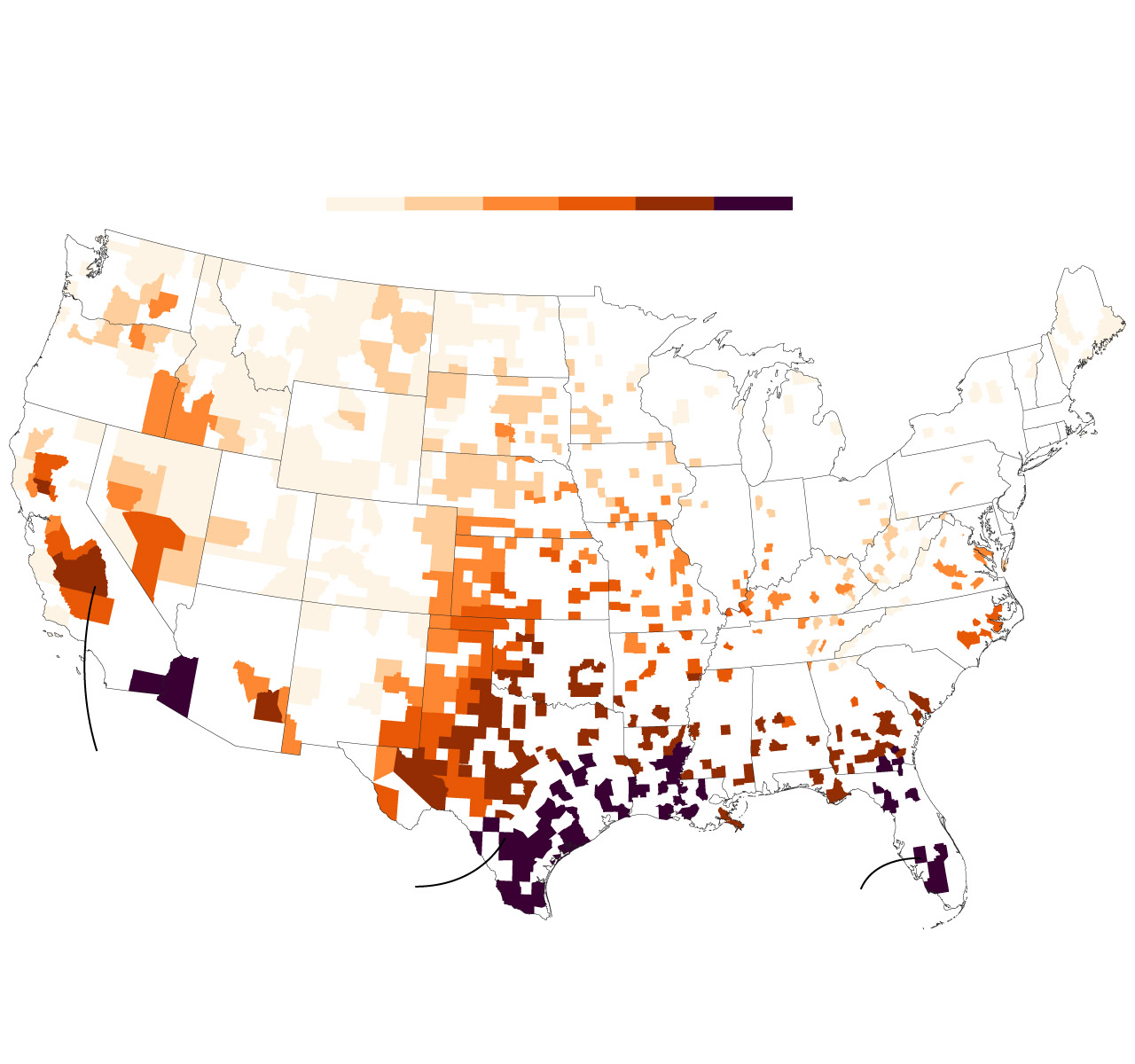

Where heat protections would have the largest impact on outdoor workers

Map shows counties where 10% or more work in construction or agriculture

Annual days with maximum heat index

of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

16% work in construction or agriculture

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

Where heat protections would have the largest impact on outdoor workers

Map shows counties where 10% or more work in construction or agriculture

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

16% work in construction or agriculture

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023. Occupational data from the American Community Survey (2017-2021).

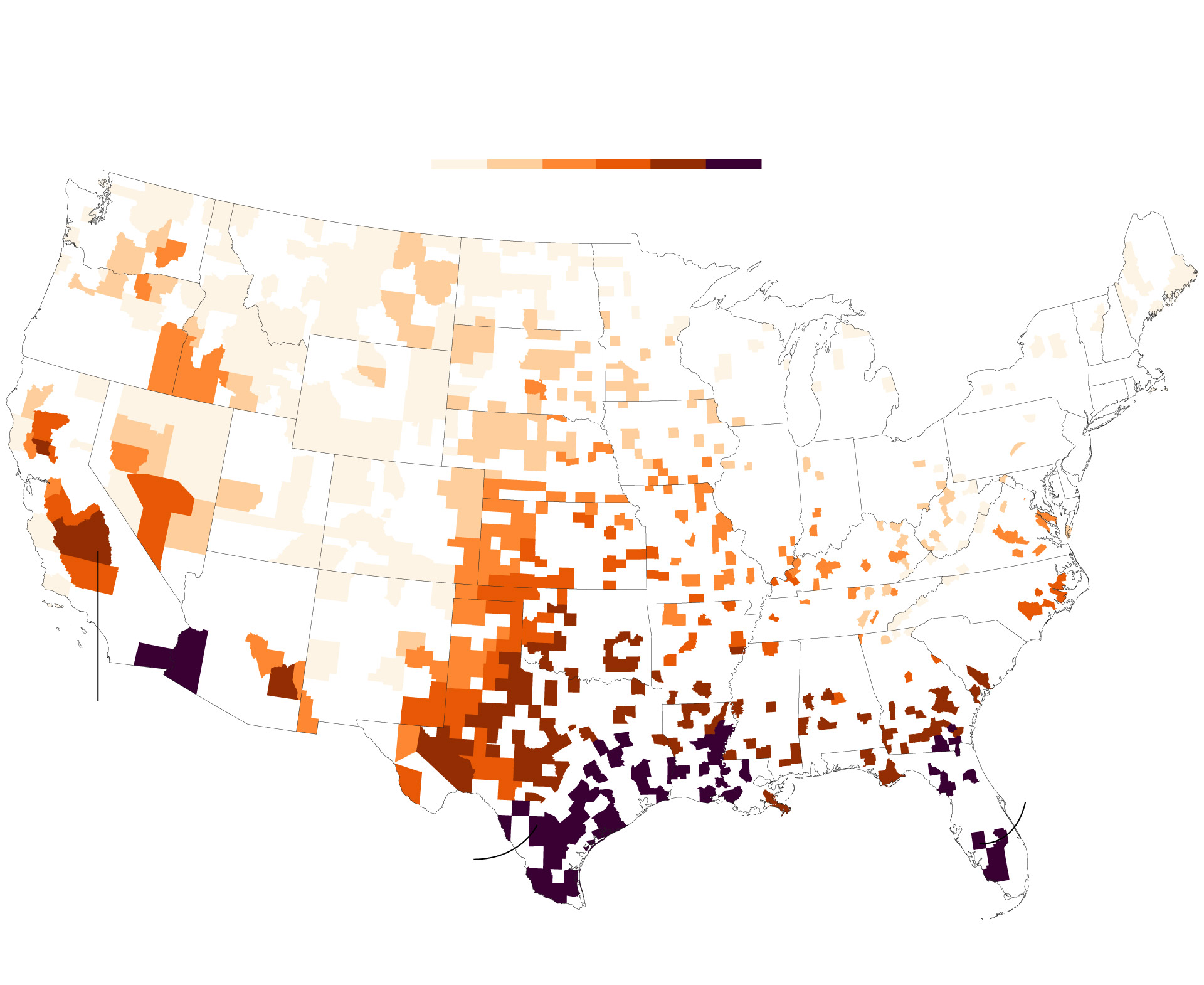

Where heat protections would have the largest impact on outdoor workers

Map shows counties where 10% or more work in construction or agriculture

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

16% work in construction or agriculture

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

Occupational data from the American Community Survey (2017-2021).

Where heat protections would have the largest impact on outdoor workers

Map shows counties where 10% or more work in construction or agriculture

Annual days with maximum heat index of 90ºF or more

Tulare County, Calif.

16% work in construction or agriculture

Source: Spangler et al., 2022 (updated 2024). Annual heat days are averages from 2013 to 2023.

Occupational data from the American Community Survey (2017-2021).

Heat index data goes beyond temperature to factor in humidity, which can intensify the impact of hot days. Such data reveals that parts of Texas, Louisiana, Florida, California and Arizona are already so hot, they would trigger the rule’s most strenuous requirements for at least four months of the year. Those are the most extreme cases, but the measure would have a much broader impact.

According to a Post analysis of heat and employment data, the rule could affect more than 500,000 agricultural workers and 4.3 million construction workers who are exposed to 30 days or more of dangerous heat each year. OSHA officials estimate it would extend new protections to some 36 million people who work indoors and outdoors.

That is the current picture. But a hotter future is certain.

Because nations have been slow to curb carbon pollution, scientists have found that temperatures will continue to climb, likely surpassing the world’s most ambitious climate target by the early 2030s. As the danger grows, more parts of the United States will likely hit OSHA’s heat triggers, requiring employers to make allowances for longer periods of time.

Veronica Carrasco, a 40-year-old construction worker, said workers need a national heat standard to protect themselves from exploitative bosses.

Carrasco works for a contractor remodeling homes in the Dallas-Fort Worth area of Texas, which has more workplace heat deaths than any other state. Her employer provides water and allows workers to take rest breaks, but the job is still arduous. Carrasco said when she works inside, her boss turns off the air conditioning so that the dust doesn’t damage the home’s HVAC system, leaving her in hot, stagnant air. When she works outside, temperatures regularly soar past 100 degrees.

“You have to imagine that it’s 110 degrees and I’m up on a 40-foot ladder with the sun beating down on my head,” she said. “It’s like working with a fever throughout my entire body.”

Some business groups say employers know best how to protect their workers from heat, and argue they have an incentive to do so, since productivity lags when workers are ill.

Yet Carrasco said she’s encountered bad bosses who ignore the risks. “I worked for four years for a boss who didn’t give us breaks and didn’t give us water, Gatorade or electrolytes — nothing,” she said. “All they care about is getting work out of you. They don’t care how hot it is.”

Carrasco has little choice but to work through the heat. After her husband died last year, she’s the only one looking after her three kids. Remodeling work slows down in the winter, she said, so she puts in as many hours as she can throughout the summer. But she worries about the risks she’s taking with her health.

“I don’t have any other family here,” said Carrasco, who immigrated to the United States from Honduras in 2011. “I have to make it back home to my kids.”

Lately, she’s started taking steps to protect herself from the heat — and uncaring employers. Three years ago, she started attending meetings of the Workers Defense Project, a nonprofit that advocates for immigrant construction workers in Texas and offers trainings on heat safety and workers’ rights.

“I’m very lucky because I learned to speak up,” she said. “When I started with this contractor [three years ago], I said, ‘This is the law. You have to give us water. I’m nobody’s slave.’”

Powerful industry groups are already working to limit the reach of a rule they view as burdensome, redundant and expensive.

A large consortium of construction and home-building companies wrote to OSHA last month, asking it to leave the construction trades out of the rule and craft a separate measure for the industry, a move that would likely delay protections for years.

“We know that [business groups] are very interested in getting their industries exempt from this rule,” said Rebecca Reindel, the safety and health director of the AFL-CIO.

Some industries have argued they are already protecting employees from heat and that a new regulation would be duplicative or, worse, get in the way of what they’re doing. They have pushed back against the rule’s expected acclimatization requirements, which would mandate a gradual ramping up of work hours during high heat. Some have questioned the entire initiative, saying that a workplace heat rule is unnecessary because not many workers die from heat exposure.

Agency officials and public health advocates say official data underestimates the scale of the problem, given underreporting and the difficulty of attributing a death to heat.

Bureau of Labor Statistics figures show that, from 1992 to 2019, an average of 32 workers died from heat-related causes annually. There were 43 such deaths in 2022, up from 36 in 2021. But workplace data aside, deaths from heat in the United States have steadily increased in recent years. An estimated 2,300 people died from heat-related illness in 2023.

A common argument from business groups is that OSHA should require heat protections to kick in at higher temperature thresholds in parts of the United States with hot and humid weather.

“One of the things that we have stressed over and over to OSHA is just that this sort of blanket threshold across the country isn’t going to work because workers are acclimatized to different regions with different varying heat and humidity levels,” said Prianka Sharma, vice president and counsel for regulatory affairs for The American Road & Transportation Builders Association. For workers in Florida and other Southern states, she said, “an 80-degree threshold for them isn’t going to be considered hot.”

In a letter sent last year to Douglas Parker, assistant secretary of labor for occupational safety and health, the industry group was dismissive of the agency’s efforts to address the growing effects of climate change on workers, writing: “OSHA policy should not be the means of achieving unrelated political talking points.”

Supporters of the heat protection rule have praised OSHA for developing standards that kick in during extreme heat, but also during moderately high temperatures. They point to research showing that even an 80-degree day can be deadly. They say the United States urgently needs a national heat standard because states where workers are the most at-risk have shown they are not going to protect workers on their own. Although five states have heat rules — California, Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington — lawmakers in Florida and Texas have passed laws blocking municipalities from enacting their own heat safety regulations.

Biden announced the proposed rule one day after Florida’s law took effect, signaling a desire to position himself as pro-labor. Many worker safety advocates and union leaders believe the outcome of the presidential election will decide the rule’s fate. Travis Parsons, director of occupational safety and health for the Laborers’ Health & Safety Fund of North America, said if Trump were to prevail, the heat standards “will be dead on arrival.”

Even if a Democrat wins the White House, other hurdles remain. Emboldened by recent decisions chipping away at the federal government’s authority to address climate change and worker safety, Republican attorneys general would likely take the heat rules to court. The Supreme Court recently rejected a lawsuit against OSHA backed by conservative and business groups, but its decision last week limiting regulatory agencies’ authority could make it easier for the rule’s opponents to challenge it.

John McAllister, a 59-year-old industrial laundry plant supervisor in Durham, N.C., said workplace heat protections would be life-changing.

Inside the cinder block building where he and about 120 other employees wash and iron, radiant heat from the machines often makes the building 10 to 20 degrees hotter than the air outdoors, he said. Although the break room is air-conditioned, McAllister said the workspace has no temperature controls. The heat has made him lightheaded and he’s seen employees break out in heat rash and become woozy.

“In the summertime, for somebody to pass out is not an irregular thing,” he said. “To be under that kind of continual heat stress, it just wears on you like a hundred-pound weight just sitting on your shoulders.”

After working at the plant for six years, McAllister can recognize the signs of heat illness. He said he jumps into action when co-workers seem disoriented or are having difficulty standing on their own. And through negotiations with his union, a local chapter of the Service Employees International Union, his employer now provides Gatorade, water and fans. Yet he would welcome clearer safety rules, especially ones requiring a cooler work area.

North Carolina doesn’t have workplace heat protections. Though state officials have said they would adopt the federal OSHA regulation when it’s finalized, lawmakers voted last year to make it more onerous to do so. Instead of being automatically adopted, new federal health and safety rules will have to be reviewed by a state commission.

“I think what’s happening in Florida and Texas, and the entire South, paints a picture of why we need federal intervention,” said Oscar Lodoño, executive director of WeCount!, a South Florida worker advocacy group that led a doomed push to create local heat protections for farm and construction workers in Miami-Dade County.

At least one company that pushed to kill the Miami-Dade County bill now supports OSHA’s effort to create national heat rules. Having one standard that applies across the United States makes more sense for companies like Costa Farms, a Miami-based tropical plant nursery that operates farms in Florida, Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, according to the company’s chief people officer, Arianna Cabrera de Oña.

“Whatever comes out of this, wherever it ends up, it’s highly unlikely that it will be perfect … but I do think that it will be something that we can live with.”