By Michael Buchanan and Katie Inman, BBC News

BBC

BBCThe experiences of a group of residents in a supported living complex in Telford illustrate the challenges facing the NHS at the moment. Many report difficulties accessing GPs, while others face long waits for hospital treatment.

The “knit and natter” mornings at the Lawley Bank Court supported living complex are noisy affairs. One resident tries to start a sing-song, belting out Ring of Fire, and though a couple of colourful blankets are on display, there is much more nattering than knitting.

Conversations vary, but there is one topic that everyone seems to have an opinion on, namely the difficulty of getting a GP appointment.

“You’re afraid to be ill,” says Brenda Stretton. “I was number 24 in the queue last week – I only got to number 19 before I was cut off. It’s heartbreaking.”

A forceful, energetic, 90-year-old, Ms Stretton had been having some eye problems but, try as she might, she couldn’t get an appointment.

Another resident, 96-year-old Gwendolyn Higgs, was similarly exasperated. A pharmacist had recommended she visit a doctor following a bout of earache.

“I went over to the receptionist last week. And she said, we’re not making appointments,” recalled the cancer survivor.

“So I said, ‘what do I have to do then to get one?’ She said, ‘ring up at eight o’clock in the morning’. So I rang up the following morning. They said they haven’t got any appointments.

“Somebody said to do it online. But they were only doing it for blood tests, not for appointments. It’s five years since I’ve been to the doctor for anything. And I still can’t get an appointment.”

What further exasperates the residents of the complex is that there is a GP surgery less than 100m from their building. Some are said to have moved in specifically because a doctor was nearby.

Even when they can get an appointment however, there is no guarantee it will be in the local practice. The surgery is part of a larger group of six surgeries, and people can be sent anywhere depending on availability. “I don’t drive,” said Ms Stretton. “So how do I get there – taxis? At £10 each?”

The cause of their frustration – as for many people around Telford – is Teldoc, a GP federation created in 2018.

“I had a case this morning, an 86-year-old lady we’ve been trying to get an appointment for, for over a week,” says Julie Vernon, who runs a company, Extra Help, that supports people with services such as cleaning and shopping.

“We phoned the GP again this morning at eight o’clock. Fully booked. So they asked us to phone 111. Phoned 111 and they called out an ambulance. The ambulance came, did an assessment and said, ‘you need a GP’. They phoned [the GP] and got one tomorrow. So that’s how many services have been involved just to get a GP appointment.”

Teldoc told us that since it was set up, there had been a large increase in the population of the town, as several housing estates had been constructed. However, it said there had been no funding to expand its services.

“Access to general practice is a national issue, and Telford is no exception,” it said in a statement. “We acknowledge that access to appointments can sometimes fall short of people’s expectations. However, we have and will continue our work to make improvements where necessary to enhance patient access to our services.”

Polling suggests that most people think public services have deteriorated nationally in recent years. This article is the third of three focusing on the town of Telford, which a BBC News analysis has identified as facing particular challenges across its courts, schools and health services. Similar problems to those found in Telford are widespread, however.

The problems across the NHS don’t simply impact the sick. The difficulty of getting appointments means schools have started letting teachers take time off during the day, forcing them to find cover in classrooms. The long delays in the back of ambulances waiting to get into A&E has led to care homes giving food parcels to residents who need to go to hospital.

“I think the NHS is broken nationally,” says Debbie Price, chief executive of Coverage Care Services, which operates 11 care homes across Shropshire. “I’ve been involved in conversations with the hospital for many years and they’re the same conversations I was having 20 years ago. Things haven’t really moved on.

She believes the way health and social care is funded needs to change. “There’s been a lot of talk about pooling resources, looking at the individual and having funding available for the individual.

“Most professional meetings are focused on solving the hospital issues though, whereas I think that social care providers – domiciliary as well as residential and nursing – can provide solutions that they just don’t consider.”

Back at Lawley Bank Court, Joyce is tending to her mother, as she does every day. Margaret, 69, has dementia and recently had a seizure that necessitated her having to go to hospital. “She was in that ambulance for nine hours,” recalls Joyce.

“She was dehydrated, she hadn’t had her medication and she was sitting in her own wee,” she adds, uncomfortable at impinging on her mother’s dignity.

Despite not having any medical training, Joyce decided the best thing for her mother was to return her home despite the fact that a doctor had not examined her.

She says: “Then I had the anxiety all night, ‘did I make the right choice? Is anything going to happen to her? Is she going to pass away?’ You shouldn’t have to go through that. I’m so scared that if she goes in again, something is going to happen to her in the ambulance. It’s just sad.”

The local hospital, the Princess Royal, has some of the longest A&E waiting times in England. Half of patients wait longer than the four-hour target to be seen, often – like Margaret – spending many hours waiting in an ambulance. Patients are routinely treated in corridors or told they are fit to sit, assessed as needing medical attention but unable to be found even a trolley.

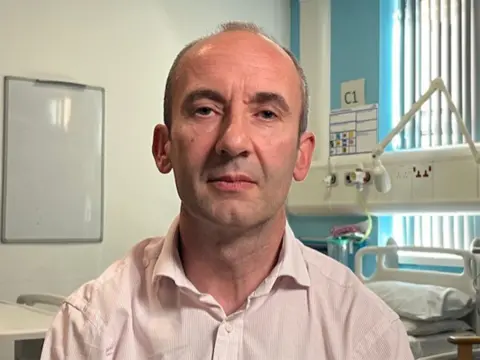

“Should people accept that? No, they should not accept any of that,” is the forthright opinion of John Jones, the medical director of the Shrewsbury and Telford NHS Trust, which runs the hospital.

The trust was at the centre of the country’s largest maternity scandal but a recent inspection by the Care Quality Commission found significant improvements in maternity care, which are now rated as Good. However, the accident and emergency unit in Telford was downgraded to an urgent treatment centre – and it is now rated as inadequate.

“We don’t need the CQC to tell us that the experience of people coming into our emergency departments is not adequate,” said Dr Jones. “Nobody could walk into an emergency department, whether it was here or anywhere else in the country, and see people being cared for in corridors or ambulances waiting outside and say this is adequate.”

There are particular factors he says that have added to the difficulties – the two hospitals the trust runs have been aiming to provide a full range of clinical services but are not big enough to do so. There have been problems recruiting staff and they have been slow in some areas to adopt new working methods.

Plans have recently been approved for the hospitals to be reconfigured – Telford’s A&E will be downgraded to an Urgent Care Centre. Dr Jones is confident the changes, including more focus on emergency treatment, will improve care.

“I think the care that we’re able to provide next winter will be better thought-through, there will be more options for people who need care. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily care in the hospital – I think part of this will be about providing some care outside of hospital. So yes, I do think patients will have a better experience.”

Additional reporting by Callum Thomson and Daniel Wainwright.