Woodcock radioed lifeguards, then activated the warning system, he later recalled, recounting the incident to a reporter. “Attention, beach users,” the drone blared. “There is a shark in your area. Please exit the water.”

As swimmers scrambled onto the beach, Woodcock’s eyes were glued to his screen, where he saw the shark following a school of fish to shore. As a wave broke, the shark suddenly surged toward the beach. Then, to everyone’s relief, it headed back out to sea.

Woodcock is one of hundreds of drone pilots enlisted in a high-tech push to stem an increase in shark attacks in Australia, a country of 100,000 beaches where most people live near the coast.

But as the number of attacks has grown recently — in Australia and around the world — the nation is moving away from traditional shark-fighting tools like nets and adopting new technologies.

Australia now has the world’s largest coastal drone-surveillance operation and is installing nonlethal traps, or drumlines, that alert authorities when a shark takes their bait. These are enabling authorities to monitor sharks like never before — and have turned Australia into a laboratory for ways to prevent shark attacks.

Drone pilots are just the beginning. Officials are testing remotely operated and long-distance drones, as well as ways to incorporate artificial intelligence. But until such technology is widely deployed, many areas remain unmonitored.

Fatal shark incidents in Australia

Source: Australian Shark Incident Database

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Fatal shark incidents in Australia

Source: Australian Shark Incident Database

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Fatal shark incidents in Australia

Source: Australian Shark Incident Database

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Woodcock’s intervention on a beach in Mollymook, three hours south of Sydney, in January at the height of the Australian summer showed the new technology’s lifesaving power. But it also revealed the gaps that remain: The great white hadn’t been tagged with a tracker, so a listening station couldn’t detect it. And had the shark appeared a few hours later, Woodcock, the sole drone operator that day, would have been off duty.

There were 10 fatal shark attacks globally last year, and four of them were in Australia, according to the University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File. Although this was lower than the six deaths in Australian waters in 2020, the trend has been up: There were only one or two fatal shark attacks a year between 2012 and 2018, with none in 2019.

Last year a woman was bitten by a bull shark in Sydney’s harbor — the first attack in the waterway in a decade. The incident and a deadly attack in Perth’s Swan River a year earlier have stirred fears that warmer waters caused by climate change are making sharks linger in some locations, just as increasing temperatures and populations drive more people to the ocean.

High above the sunbathers and bodybuilders of Bondi Beach sits an Aboriginal rock carving showing what may be humankind’s first recorded shark attack. British colonists found Sydney harbor “full” of the animals. And when Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, visited in 1920, he marveled that “the fact that the water swarms with sharks seems to present no fears to these strong-nerved people.”

Yet, even those strong nerves have occasionally frayed. When attacks increased in the 1930s because of waste near Sydney’s shore, authorities put nets around popular beaches.

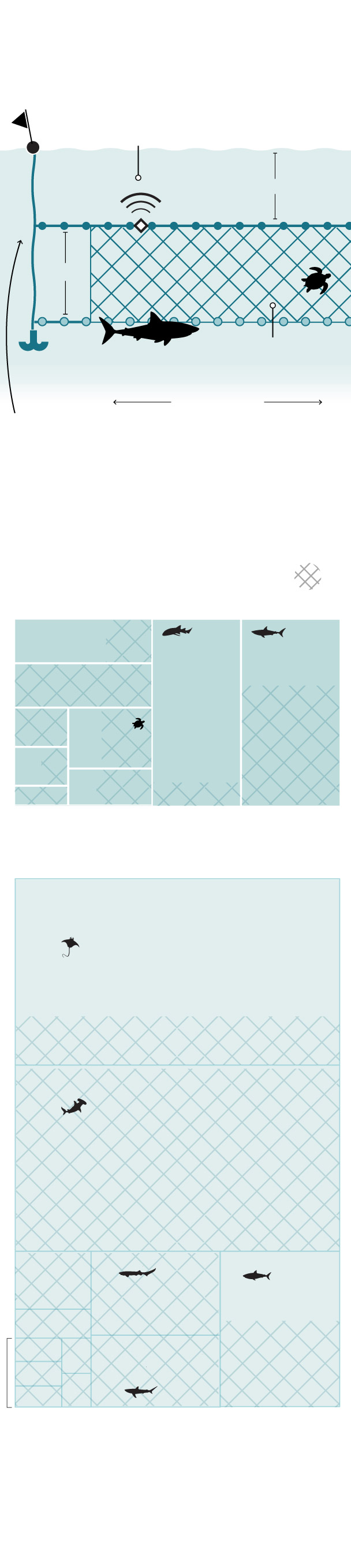

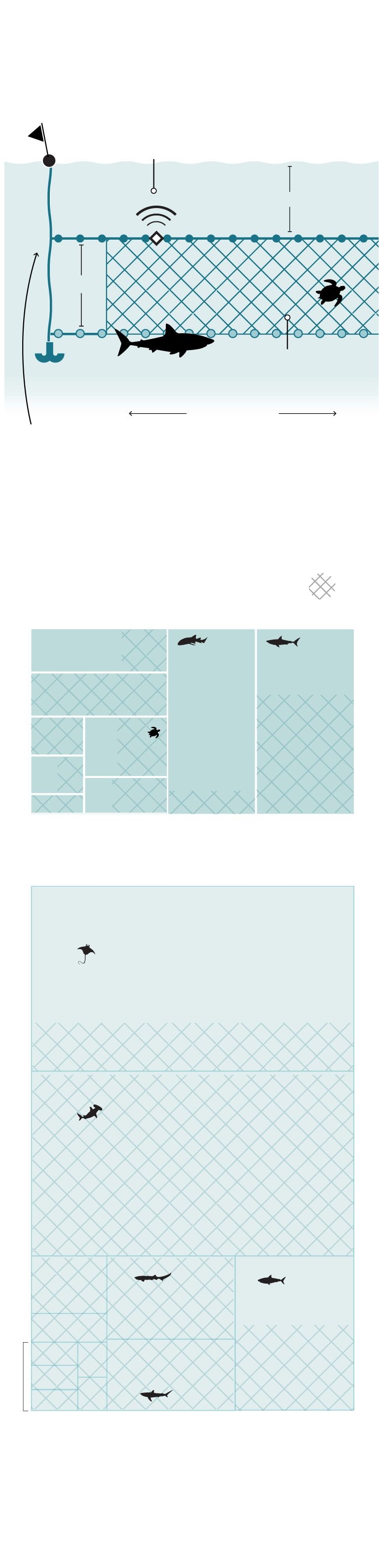

Nearly a century later, the nets are still in place: There were 51 along 150 miles of coastline near Sydney this Australian summer, managed by the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries.

State workers check the nets every few days. “Target species” — great white, tiger and bull sharks, which cause most of the serious bites — found alive are fitted with acoustic tags and shepherded out to sea. But most wildlife caught aren’t sharks, let alone dangerous ones, and are already dead by the time they are discovered.

Whale alarms

and dolphin pingers

aimed to deter

mammals.

The nets do not

create an enclosed

area.

Animals entangled in the nets

From Sept. 1st, 2022,

to April 30, 2023.

Indo-Pacific

bottlenose dolphins

Broadnose

sevengill

sharks

Australian angel

Spinner shark

Longtail tuna

Yellowfin tuna

Unidentified

whaler shark

Source: NSW Department of Primary Industries

Whale alarms

and dolphin pingers

aimed to deter

mammals.

The nets do not

create an enclosed

area.

Animals entangled in the nets

From Sept. 1st, 2022,

to April 30, 2023.

Indo-Pacific

bottlenose dolphins

Broadnose

sevengill

sharks

Australian angel

Spinner shark

Longtail tuna

Yellowfin tuna

Unidentified

whaler shark

Source: NSW Department of Primary Industries

Whale alarms

and dolphin pingers

aimed to deter

mammals.

The nets do not

create an enclosed

area.

Animals entangled in the nets

From Sept. 1st, 2022, to April 30, 2023.

Broadnose

sevengill

sharks

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins

Australian angel

Spinner shark

Longtail tuna

Yellowfin tuna

Unidentified

whaler shark

Source: NSW Department of Primary Industries

Whale alarms

and dolphin pingers

aimed to deter

mammals.

The nets do not

create an enclosed

area.

Animals entangled in the nets

From Sept. 1st, 2022, to April 30, 2023.

Broadnose

sevengill

sharks

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins

Australian angel

Spinner shark

Longtail tuna

Yellowfin tuna

Unidentified

whaler shark

Source: NSW Department of Primary Industries

“Shark nets create an incredible cost on other marine life,” said Duncan Heuer from Saving Norman, a group devoted to Bondi’s critically endangered gray nurse sharks.

But the biggest argument against nets is that they don’t work, he says. They sit about 13 feet below the surface, end well above the ocean floor and are only 500 feet long. Nearly half the time that a shark gets caught, it’s already on the shore side of the net, he added. And 17 percent of unprovoked attacks have happened at netted beaches, according to DPI.

Nets give beachgoers false security, making politicians reluctant to get rid of them, said Chris Pepin-Neff, an expert on the public policy of shark attack prevention. “It’s smoke and mirrors,” they said.

DPI still says nets reduce shark encounters, but its stance has softened. A recent study whose authors included DPI scientists said it “could not detect differences in the interaction rate” between sharks and humans at netted vs. non-netted beaches since the early 2000s. Last year, half the communities with nets voted to remove them.

Ultimately, it’s the state government that will decide. New South Wales Premier Chris Minns wants to get rid of the nets — with a caveat. “I’ve got to have confidence that the replacement, the new technologies, are as good,” he said last year.

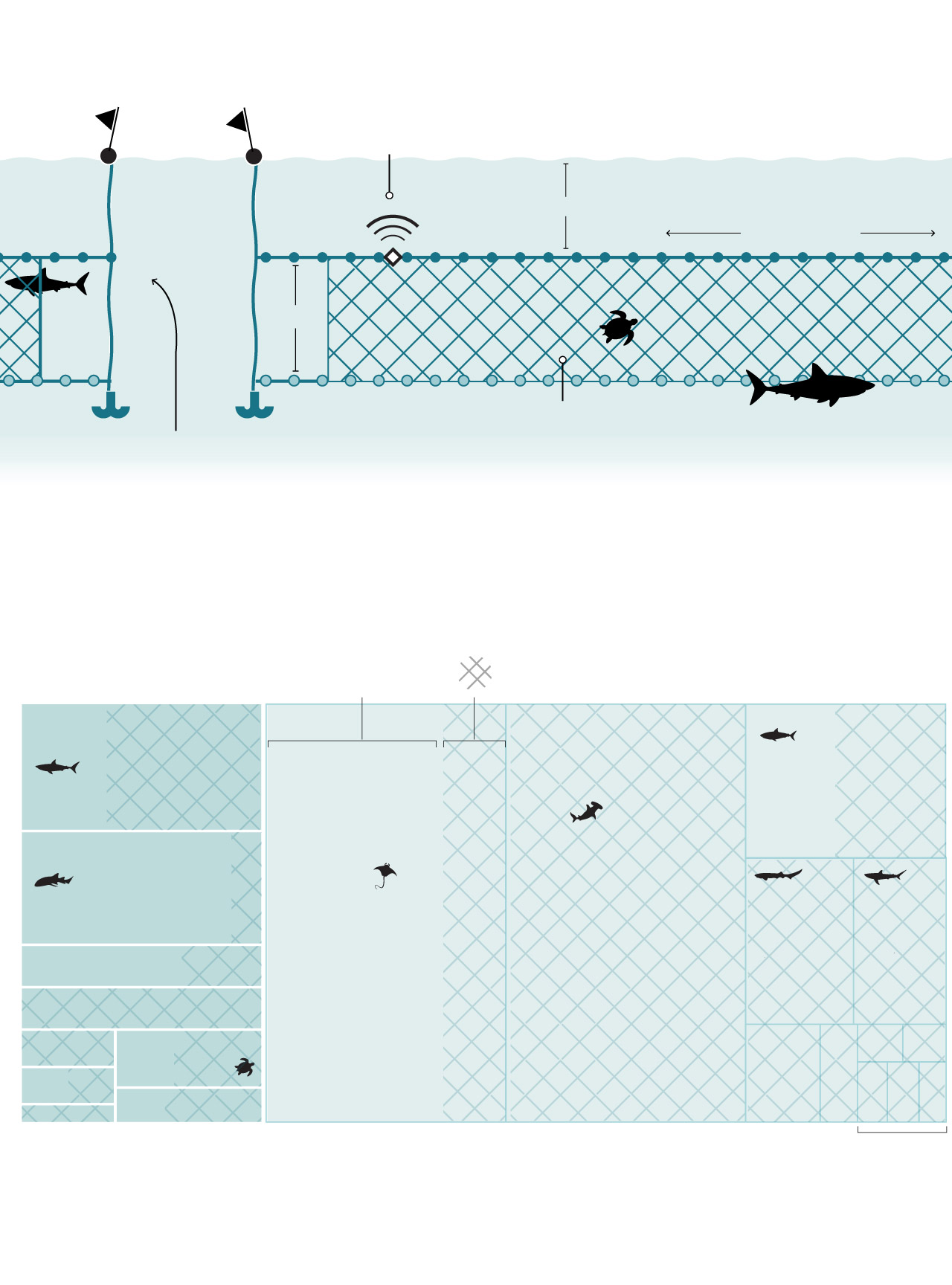

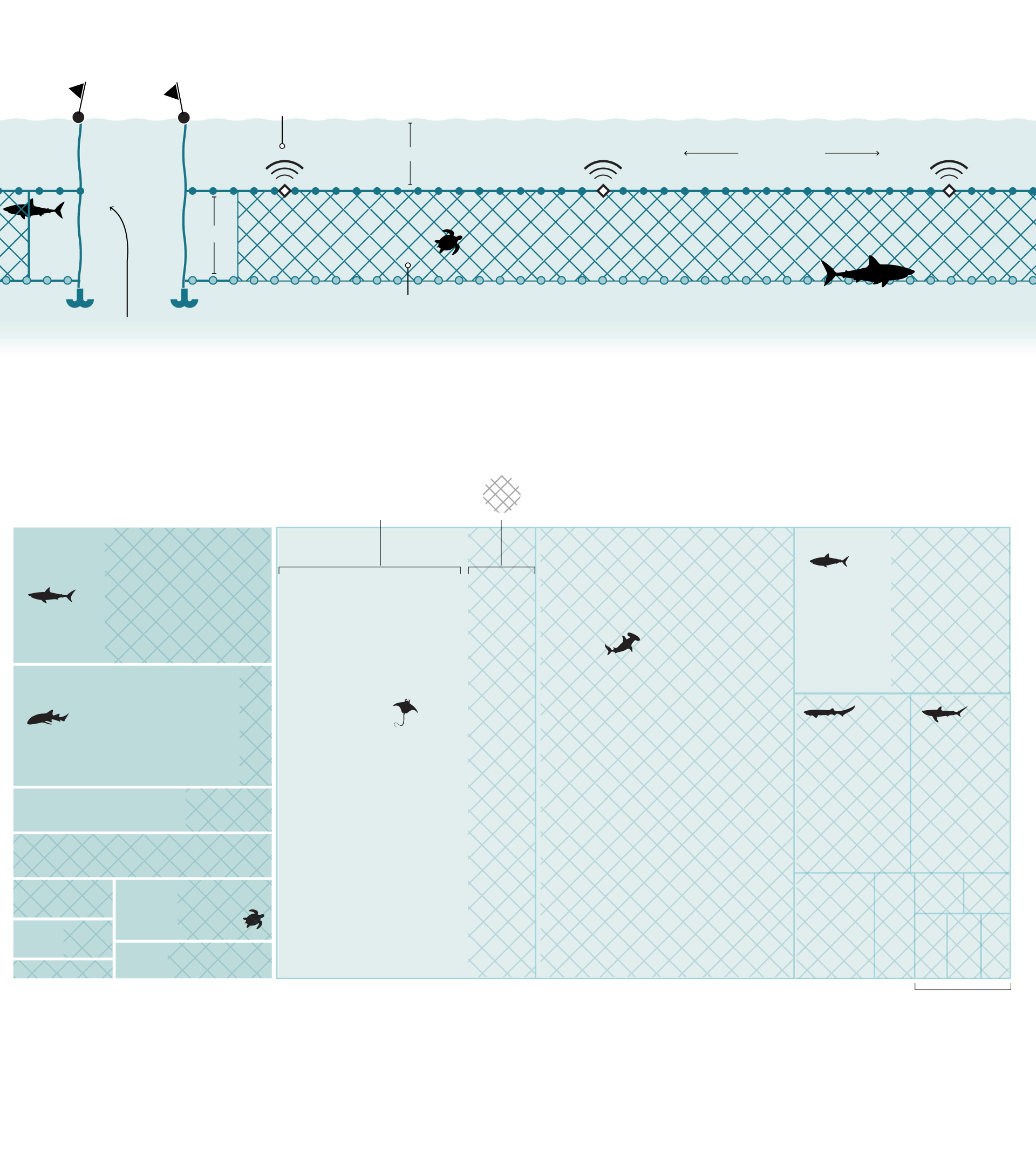

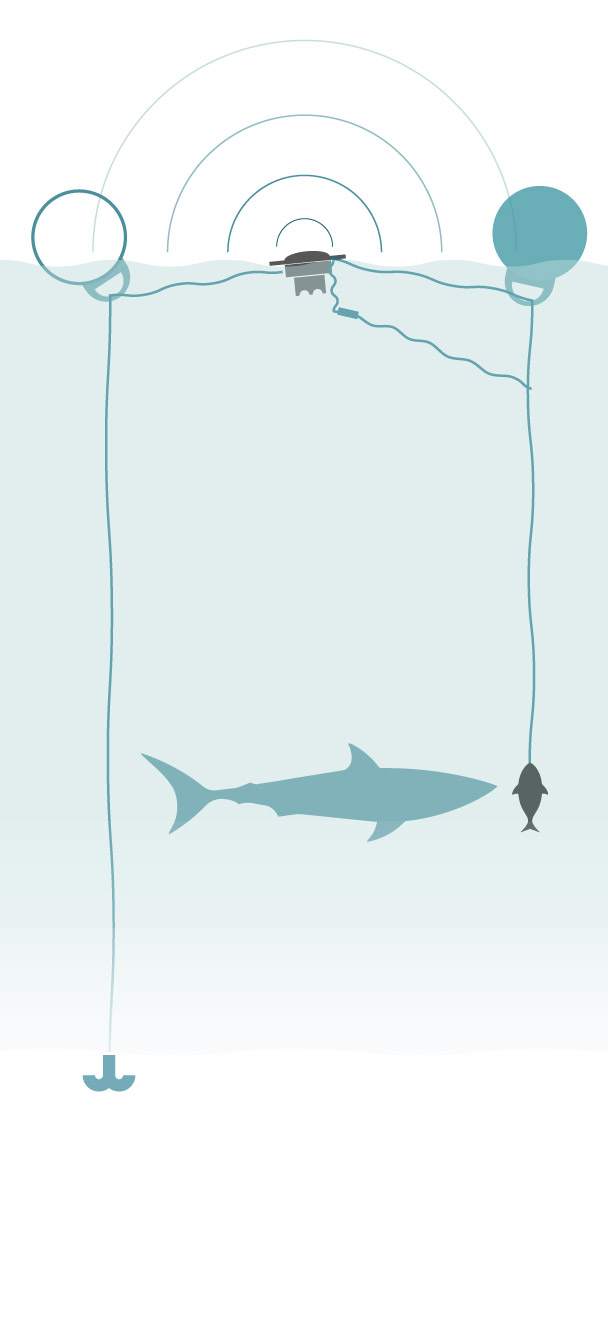

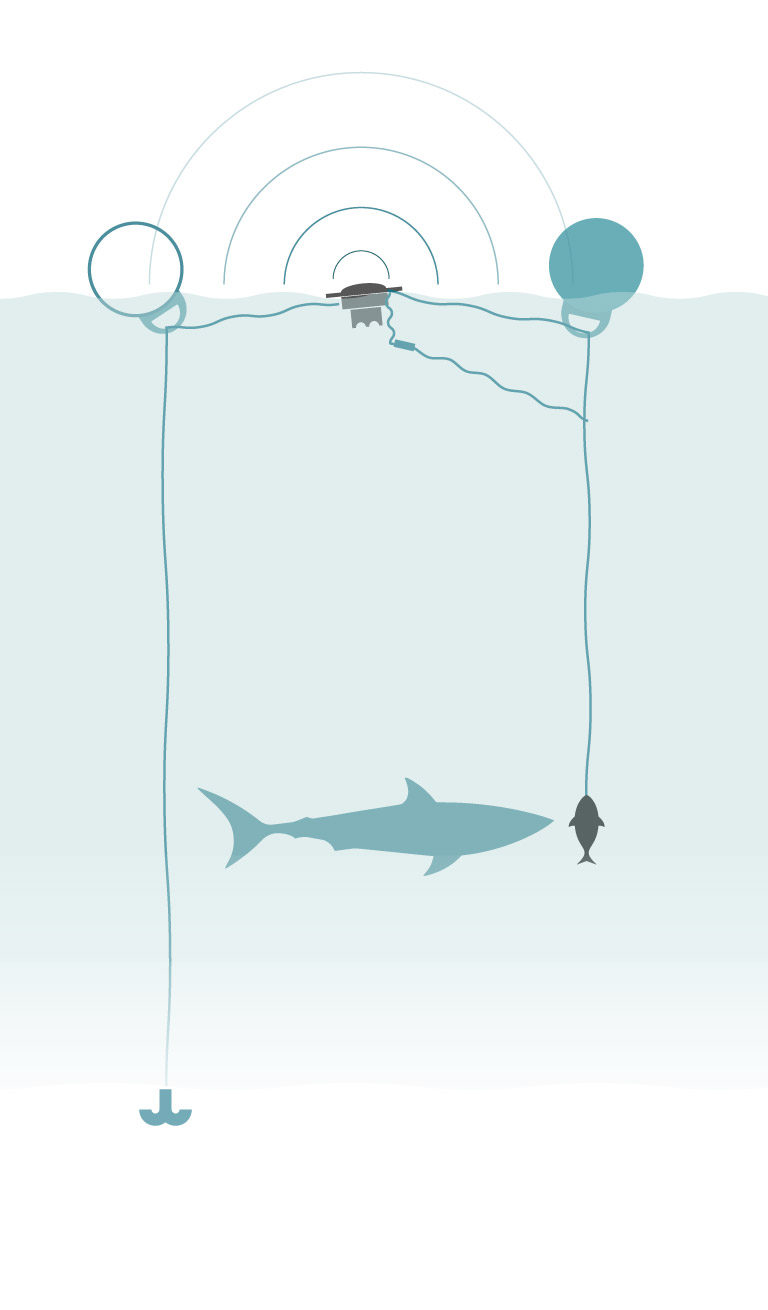

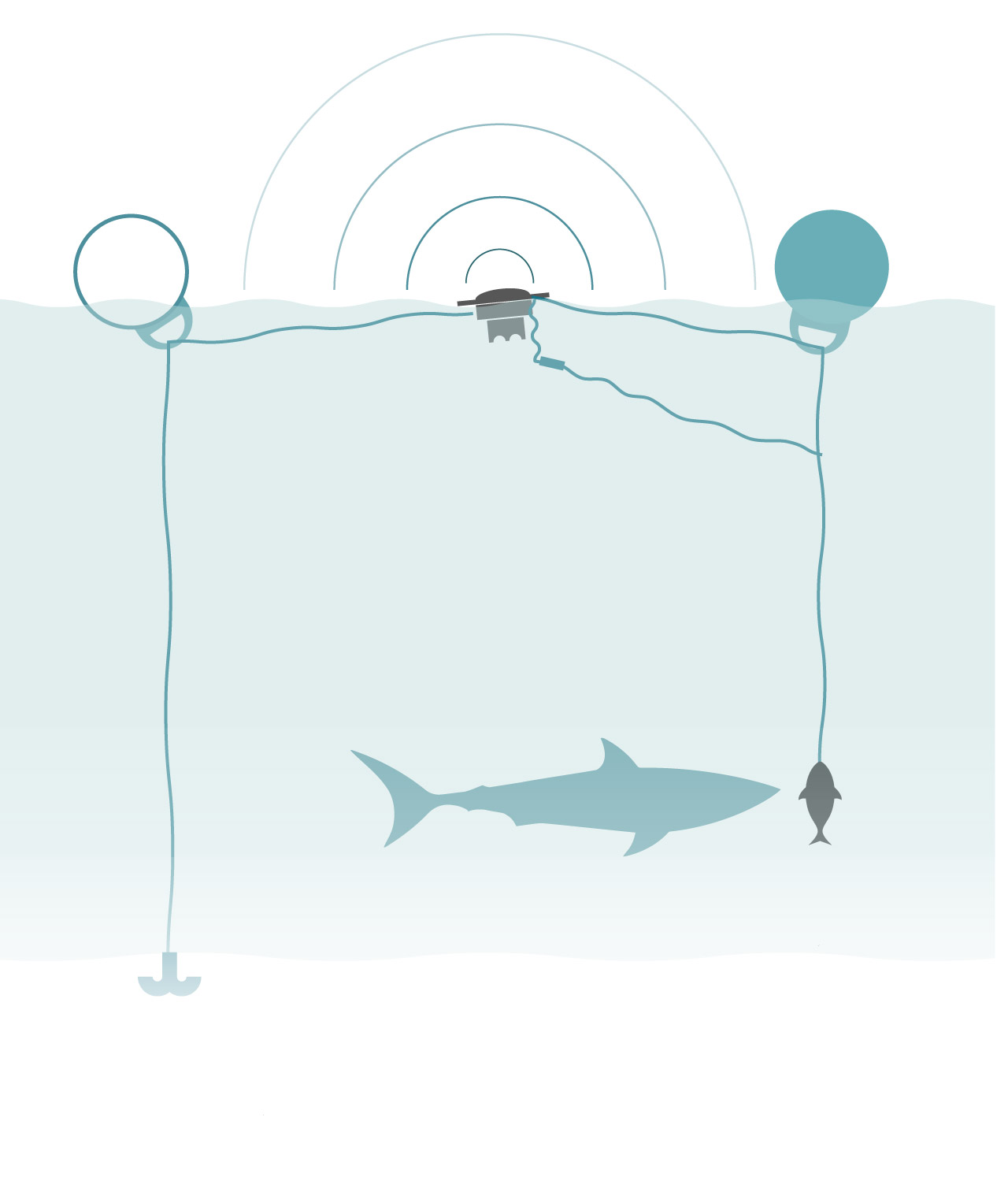

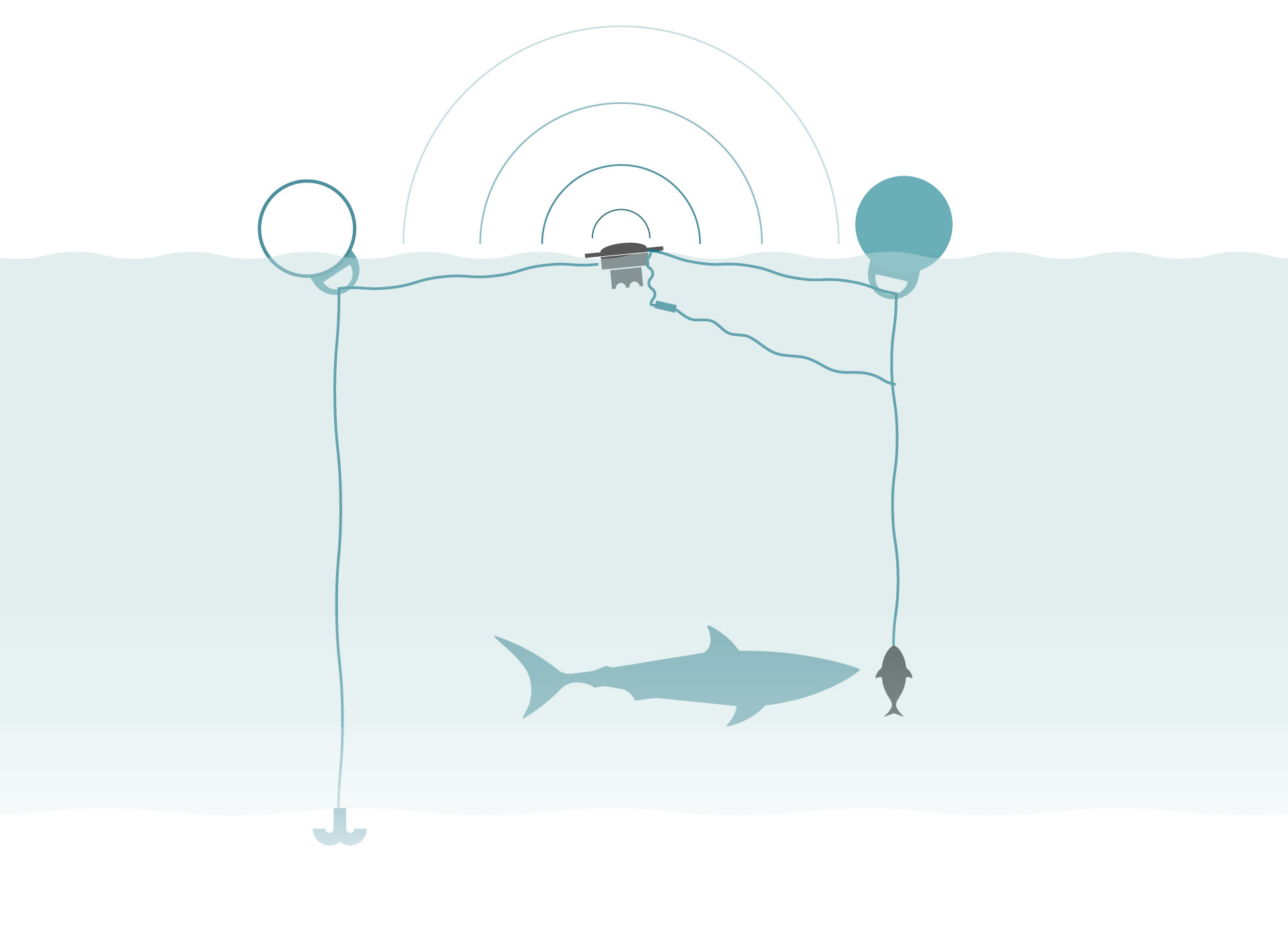

On a muggy morning in late January, that new technology lined the deck of a small fishing boat chugging out of the Coffs Harbour marina, 300 miles north of Sydney. As dawn streaked the sky, Samara Bye tossed an anchor over the side of the boat. Then she threw in two buoys attached to a solar-powered, satellite–linked sensor. Finally, she chucked in a mullet on a six-inch hook.

She was fishing for sharks.

The DPI contractor was setting 15 nonlethal, or “SMART,” drumlines. (“SMART” stands for “Shark Management Alert in Real Time.”)

When a shark takes the bait, it sets off the sensor, alerting officials, who speed to the site within 30 minutes.

As with the nets, if the animal is a great white, tiger or bull shark, it’s tagged and taken a half-mile out to sea to be released. If it’s anything else, it’s let go immediately.

When a shark takes the bait, it sets off the sensor, alerting officials, who speed to the site within 30 minutes.

As with the nets, if the animal is a great white, tiger or bull shark, it’s tagged and taken a half-mile out to sea to be released. If it’s anything else, it’s let go immediately.

When a shark takes the bait, it sets off the sensor, alerting officials, who speed to the site within 30 minutes.

As with the nets, if the animal is a great white, tiger or bull shark, it’s tagged and taken a half-mile out to sea to be released. If it’s anything else, it’s let go immediately.

When a shark takes the bait, it sets off the sensor, alerting officials, who speed to the site within 30 minutes.

As with the nets, if the animal is a great white, tiger or bull shark, it’s tagged and taken a half-mile out to sea to be released. If it’s anything else, it’s let go immediately.

“People hear ‘drumline’ and think we’re killing the sharks, but we’re not,” said Paul Butcher, a DPI scientist. He contrasts the technology to Queensland state’s use of traditional drumlines, which are left overnight, are deadly and have drawn outrage.

The new drumlines were first implemented in New South Wales in 2015, after four shark attacks — one fatal — in as many weeks sparked fear in the normally laid-back surfer communities near Byron Bay, north of Coffs Harbour. “The feeling was, ‘You’ve got all those shark nets down in Sydney, but what are you doing for us up here,’” recalled Liz Brennan, a communications coordinator for DPI.

The program, which has grown from a few drumlines to 305, helps keep people safe: Sharks tend to avoid for a few months places where they’ve been caught, Butcher said. But it also helps humans learn about the animals via DNA and tracking data.

The drumlines work with 37 listening buoys, which alert lifeguards and some beachgoers when a tagged shark approaches.

The idea is to eventually replace Sydney’s shark nets with the newer, nonlethal technologies.

“There just has to be a government at some stage that, when they are happy with the research, will swap shark nets out for drumlines and drones,” Butcher said.

The new tech isn’t perfect. Sometimes the drumlines have false alarms. Glare or seagrass can prevent drone pilots from spying sharks, while bad weather can ground some machines. And drones are only as good as their operators, who must stay alert for hours.

“It’s a lot of coffee,” Paolo Cattaneo, another drone pilot, explained as he scoured the waves at Tamarama, not far from Bondi. Like the drumlines, the drone program has grown from a small experiment in 2017 to the biggest such operation in the world. More than 200 paid pilots monitor 50 locations along the state’s coast from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. during four busy school-holiday periods. There are also has a few hundred year-round volunteers.

New South Wales used to use planes, which released red powder if they spotted a shark, said Pepin-Neff. Then the state switched to helicopters, but they proved expensive and ineffective.

As on the battlefield, drones are proving cheaper and more efficient on the beach. If Cattaneo spots something, he drops his drone to 50 feet and starts recording. Shark diagrams on his monitor help him gauge an animal’s size. If it’s a great white, tiger or bull shark and it gets within about 1,000 feet of the beach, he’ll tell lifeguards to clear the water. In the six weeks over Christmas, as the Australian summer was in full swing, drone pilots spied 164 sharks.

DPI is experimenting with AI to help drone pilots identify dangerous species. It is also testing “drones in a box” — stored at beaches and deployed remotely — and long-range drones that can fly for 60 miles.

It’s too soon to say if this will stem rising shark attacks. But so far, in five years, there hasn’t been a shark-human interaction at a beach protected by either drones or the new drumlines, compared with 19 in a similar period before.

Some warn against putting too much faith in technology, however. The program costs New South Wales about $14 million a year, more than many places can afford. And even in the future, if Australian beaches are continually patrolled by drones, it still won’t be possible to prevent every shark attack.

“When you enter wildlife’s domain,” Pepin-Neff said, “you do it at your own risk.”