Beneath the posturing, though, there are growing fears within Israel that its soldiers are overstretched and its resources depleted after the country’s longest war in decades. Nine months of punishing attacks against Hamas in the Gaza Strip have not vanquished the group, and a politically embattled Netanyahu has yet to outline an exit strategy. In Lebanon, Israel would face a larger, better-armed and more-professional foe, experts warn, and the threat of an even deeper military quagmire.

Israel has been fighting on two fronts since Oct. 8, the day after Hamas-led militants assaulted southern Israel, killing about 1,200 people and taking more than 250 hostages. Within hours, fighters from Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed political movement and militant group that is allied with Hamas, began launching attacks on northern Israel from Lebanon — the start of a tit-for-tat border conflict that has escalated, and spread deeper into both countries, with each passing month.

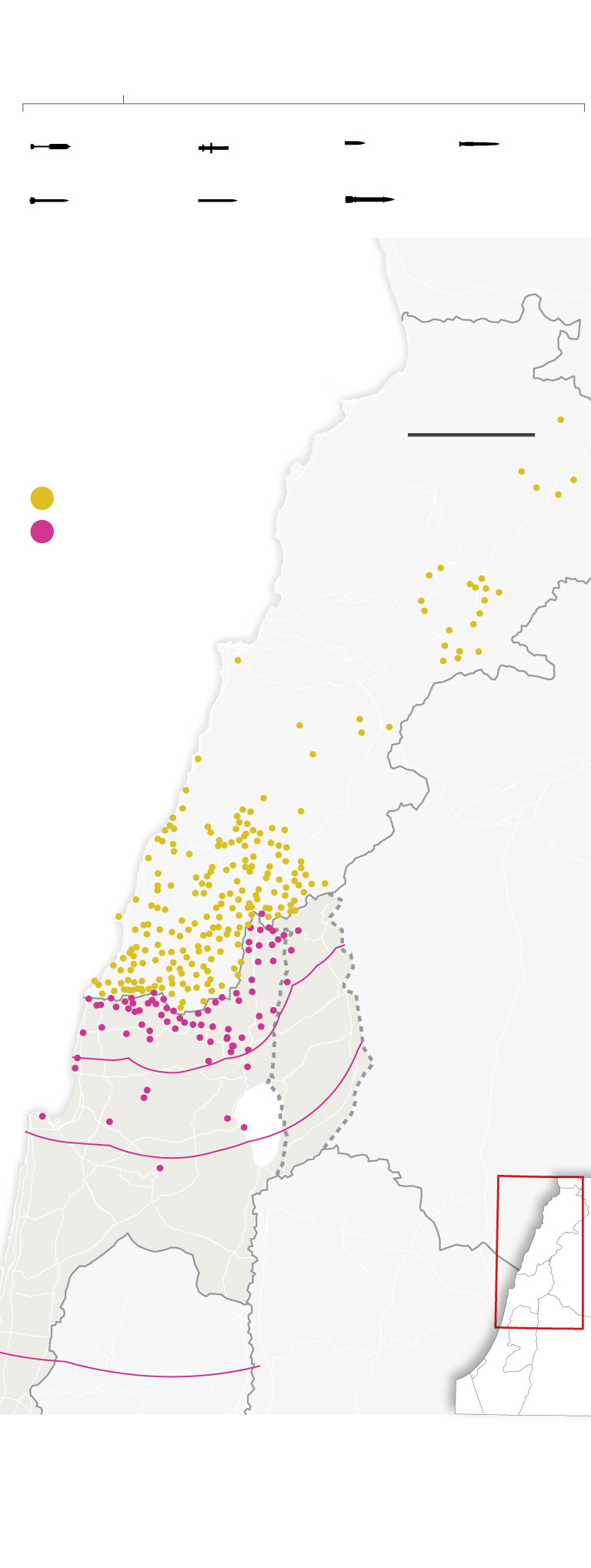

Hezbollah’s known rocket and missiles

Max. range (in miles)

Reported attacks since Oct. 7

Incidents include airstrikes and

shelling, as well as drone, artillery

and missile attacks.

Note: The Golan Heights were seized by Israel in 1967

and illegally annexed in 1981.

Source: ACLED. Data as of June 28

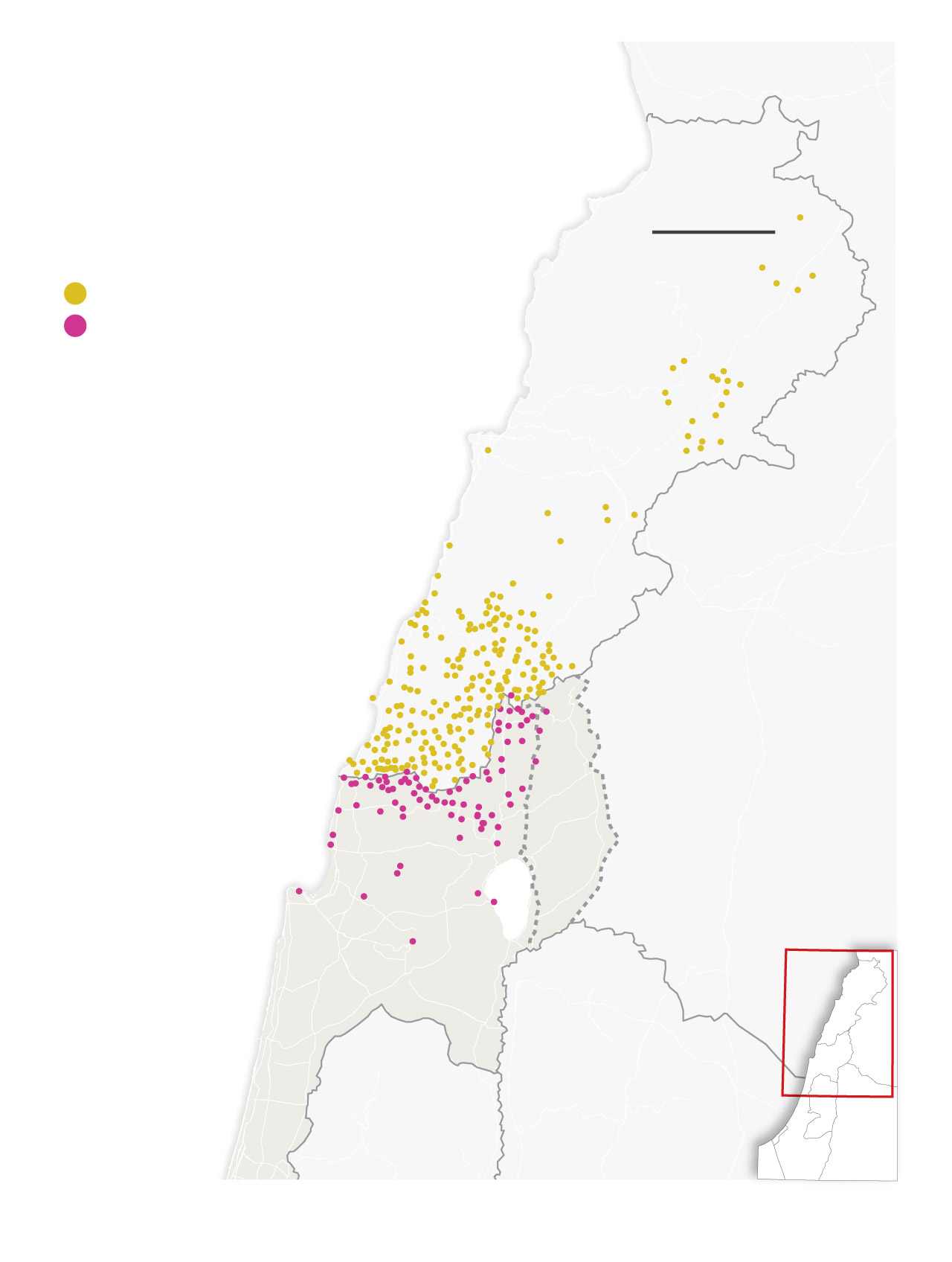

Hezbollah’s known rocket and missiles

Max. range (in miles)

Reported attacks since Oct. 7

Incidents include airstrikes and

shelling, as well as drone, artillery

and missile attacks.

Note: The Golan Heights were seized by Israel in 1967

and illegally annexed in 1981.

Source: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Data as of June 28.

Reported attacks since Oct. 7

Incidents include airstrikes and

shelling, as well as drone, artillery

and missile attacks.

( Annexed by Israel

in 1981. Not internationally

recognized.)

Source: Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Data as of June 28.

Israel says it is transitioning to a less intensive combat phase in Gaza, and it has resumed negotiations in Cairo over a possible hostage-release deal. But Hezbollah insists it will not lay down its arms, or consider retreating from the Israeli border, until a cease-fire is in place in the Strip.

Both Israel and Hezbollah say they would prefer a diplomatic solution, but neither seem prepared to make the kind of concessions such a solution would require. The result is a strained stasis, with death tolls mounting; border towns standing abandoned, their fruit trees and dairy farms untended; and pressure building from Israel’s displaced for the government to act.

Israeli military leaders have been drawing up plans for a Lebanon offensive for months. On Wednesday, a day after two Israeli civilians were killed in a Hezbollah missile barrage, former war cabinet member Benny Gantz said that he and others had demanded that Netanyahu authorize an Israeli incursion into Lebanon in March, but that the prime minister “hesitated” — refusing to commit to returning Israeli residents to their homes in the north by Sept. 1, the start of the new school year.

GET CAUGHT UP

Stories to keep you informed

“Israel cannot afford for the events in the north to go on as they are, to lose another year,” Gantz said. “The time has come for the price to be paid in military targets and Lebanese infrastructure, of which Hezbollah is a part.”

Netanyahu, who once boasted of his ability to prevent wars, “knows that the Israeli public is not prepared for thousands of rockets on Tel Aviv,” said Gayil Talshir, a political scientist at Hebrew University.

Instead of strategizing, she said, he has “isolated” himself, avoiding hard decisions in order to buy time and surrounding himself with loyalists lacking military expertise.

Since dissolving his war cabinet, after Gantz’s recent departure, Netanyahu has distanced himself even further from the army brass, analysts say, including Gallant, who has pushed for months for a cease-fire and hostage deal in Gaza to allow the military to focus on Lebanon.

“These are critical days in terms of exercising our power against [Hezbollah], which only responds to force,” Gallant said Sunday as dozens of missiles fell on Israel, including at a strategic military base on Mount Meron.

The few Israelis who stayed in northern Israel after Oct. 8 to defend the border did not expect to be in limbo for so long.

“The families are tired,” said Omer Simchi, who has served for nine months on the local defense squad of Kibbutz Sasa, an Upper Galilee agricultural commune a mile from the Lebanese border.

Simchi’s wife and two young children were among nearly 100,000 Israelis who evacuated northern Israel as Hezbollah rockets, kamikaze drones and antitank missiles began raining down last year, transforming this pastoral mountain region into a conflict zone. Similar numbers of Lebanese have been displaced by Israeli attacks across the south of their country.

At least 94 civilians and more than 300 Hezbollah fighters have been killed in Israeli strikes in Lebanon; Hezbollah attacks have killed at least 20 soldiers and 11 civilians in Israel.

Simchi finds a replacement on the squad when his family needs him, but there are never enough volunteers.

“I don’t know if there will be a diplomatic agreement or a war, but what I do know is that it cannot go on like this,” he said, speaking in the kibbutz’s school auditorium, destroyed by Hezbollah missiles in December.

Local council head Moshe Davidovich said hundreds of homes have been damaged or destroyed across northern Israel.

It is only a small glimpse of the destruction Hezbollah would be likely to inflict in a full-scale war — expected to bring widespread power outages, massive rocket and missile barrages, and intense ground combat against well-trained and well-equipped fighters battling on familiar terrain. Hezbollah is believed to have more than twice as many fighters as Hamas, and more than four times as many munitions, including guided missiles. Concerns that Israel is unprepared are now being voiced openly.

“The reserves and the regular army system have been worn to the bone,” Yair Golan, leader of Israel’s Labor party and a former deputy chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, told an Israeli radio station last month.

“Israel is used to fighting short wars,” said Yoel Guzansky, a former official on Israel’s National Security Council and now a senior fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies. “But after nine months, the IDF is exhausted, the equipment needs to be taken care of, the munitions have been used up, and every family in Israel is affected by it.”

Even the relatively low-intensity conflict along the border has taken a heavy toll on front-line soldiers. A 25-year-old Israeli reservist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity in line with military protocol, was deployed to northern Israel on Oct. 7. Under fire for four months, the “burnout” accumulated, he said.

When his tour ended, “it was hard to return to routine,” he said. He guiltily asked for a break from his job as a teacher so he could readjust to civilian life.

Now preparing to be called up again, he wonders if he is up to it. His friends, he says, are also wrestling with the decision.

Since the start of the operation in Gaza, 325 Israeli soldiers have been killed, more than four times the toll from the 2014 war against Hamas. The losses have been compounded by a mounting sense of strategic failure. In late winter, Israel returned most of its reservists home without achieving either of its stated war goals: the destruction of Hamas and the return of the more than 100 hostages that remain in Gaza.

More than 38,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, which does not distinguish between combatants and civilians but says the majority of the dead are women and children.

An Israel-Lebanon war would be disastrous for both sides, experts say.

After publishing drone footage last month of the port in the Israeli city of Haifa, Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrallah warned of a war “without rules and without ceiling.” On Tuesday, Israeli Foreign Minister Israel Katz posted on X: “Nasrallah, if you don’t stop the threats and violence and withdraw to the Litani River, you will be considered the destroyer of Lebanon.”

But an Israeli invasion of Lebanon could be a “trap,” said Guzansky, pulling Israel into another grueling war with no endgame.

“There is a false belief in Israel that a war there could be finished in a number of days or weeks,” he said.

Scenes of devastation in Lebanon would also intensify international pressure on Israel and increase tensions with Washington.

Last month, Netanyahu said that there had been a “dramatic decline in weapons deliveries from the U.S. to Israel,” and that only “a trickle” had been delivered since — a claim strenuously denied by American officials. On Wednesday, U.S. officials said that some of the bombs held up since May were now en route to Israel.

To avert a Lebanon war, Israeli officials are demanding — through U.S. and European diplomats — that Hezbollah retreat about 10 miles north of the border, past the Litani River, a military demarcation agreed upon at the end of the 2006 war.

Darina Kalabrino, a resident of Kibbutz Sasa, was living in the nearby city of Kiryat Shmona in 2006 and hid in the bomb shelter as her home was hit by a Hezbollah missile. In 2018, the Israeli military said it had uncovered Hezbollah plans to “conquer” the Galilee. It found several cross-border tunnels, though residents believe that there are many more.

Kalabrino says her greatest fear is the kind of mass infiltration and massacres experienced in the southern kibbutzim.

“We need to not become the next Oct. 7,” she said. “We saw what can happen with our own eyes.”

Suzy Haidamous in Beirut contributed to this report.