Last Updated:

From Ladakhi foodways to community-led curation, Journeying Across the Himalayas explored how Himalayan voices, traditions and lived experiences are reclaiming their own narratives

Book launch of The Great Himalayan Exploration – The Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Eastern Himalayas (a UNESCO × Royal Enfield project)

At Travancore Palace this December, Journeying Across The Himalayas unfolded not as a festival that simply showcased the mountains, but as one that listened to them. Across installations, performances, workshops and food, the second edition of Royal Enfield Social Mission’s multidisciplinary festival foregrounded a crucial shift in cultural storytelling: moving from representation to authorship. Anchored in the theme “Ours to Tell,” the festival positioned Himalayan communities not as subjects of curiosity, but as narrators of their own histories, ecologies, and living traditions.

For Bidisha Dey, Executive Director of Eicher Group Foundation, this wasn’t just a curatorial idea, it was a commitment. “Programming was shaped to shift authorship back to Himalayan communities,” she explains. Artists, artisans, musicians, pastoralists, youth fellows and practitioners didn’t merely participate; they co-created. Exhibitions, performances and conversations emerged from lived realities rather than external interpretation, ensuring that what visitors encountered was grounded in experience, not romanticisation.

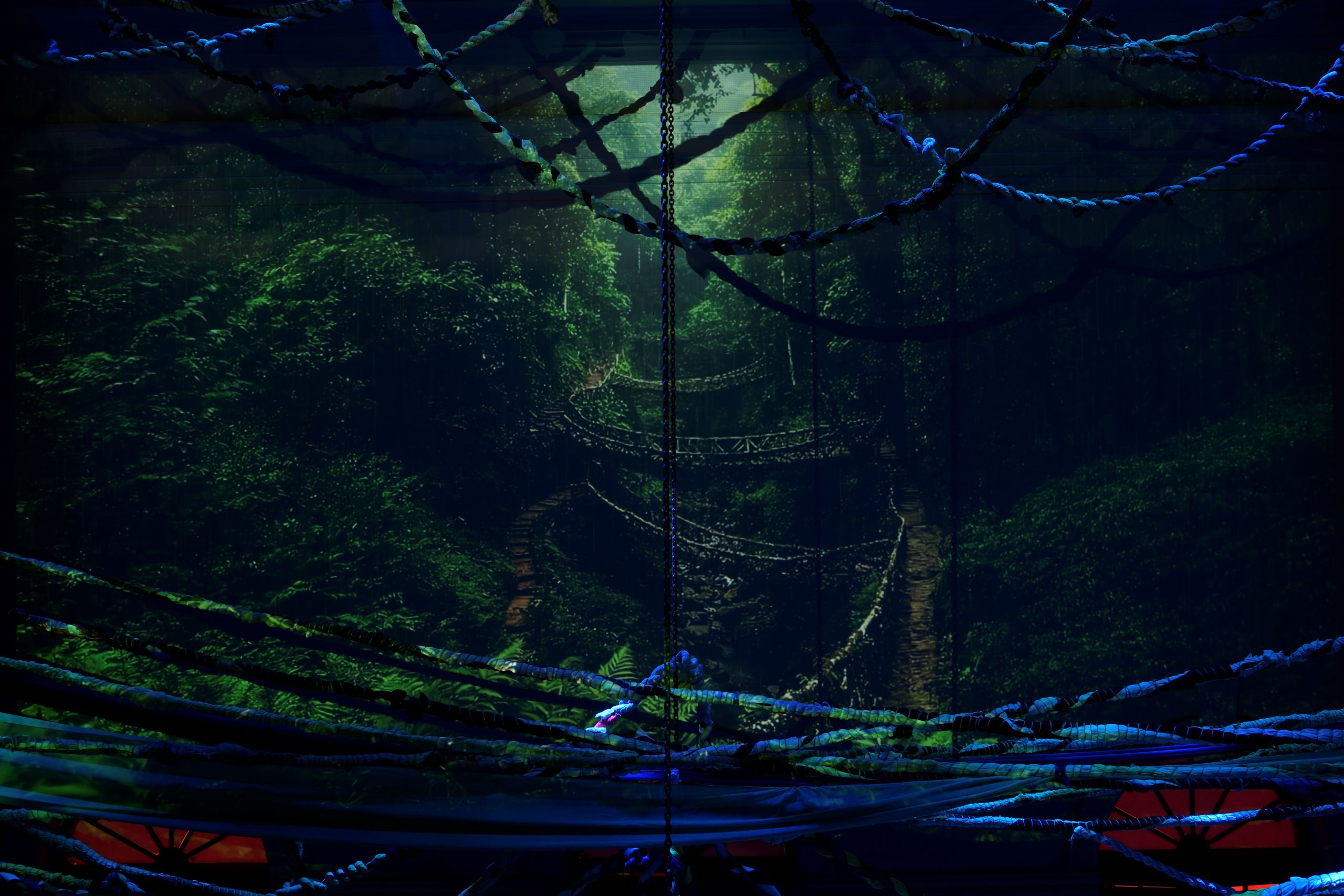

That ethos was evident across the festival’s physical language. Architectural references drawn from Kath Kuni homes of Himachal Pradesh, indigenous Adi structures from Arunachal Pradesh, and ecological systems like Meghalaya’s living root bridges created portals into ways of living rather than symbolic backdrops. At the heart of it all was the metaphor of the hearth, a communal space where food, stories and ideas circulate freely. It was here, in this space of exchange, that culinary experiences became some of the festival’s most powerful storytellers.

One such voice came from Kunzes Angmo, founder, Artisanal Alchemy, whose immersive culinary experience Stendel offered a rare, deeply considered entry into Ladakh’s foodways. For Angmo, food is not a performance but a philosophy. Stendel, a Ladakhi term, denotes a sustained, harmonious interdependence between living and non-living beings, rooted in non-violence, compassion and ecological balance. “It forms the bedrock of Ladakhi culinary heritage,” she says, “and traditionally, our entire way of life.”

Her table became a microcosm of Ladakh itself. Indigenous root vegetables like gya-labuk (Chinese radish) and tramnyung (rutabaga), sun- and shade-dried as they would be in winter back home, were laid out for audiences to touch, smell and where possible; taste. Live demonstrations of shaping noodles and pastas used in dishes like skyū, chhutagi and various thukpas transformed technique into memory-in-the-making. “Taste and smell,” Angmo believes, “are the most powerful ways to experience and remember a place.”

That belief carried through into a thoughtfully curated takeaway tiffin, designed for speed and simplicity, but rich in meaning. Winter bread tsong thalshrak paired with muskot from Balti cuisine; fermented khambir with apricot conserve; kushu pheymarr made from indigenous barley and apple flour; steeped apricots; and a Ladakhi trail mix of kernels, dried cheese, seeds and nuts sourced from villages like Takmachik and Sakti. Each element traced a geography, a season, a technique, and a lineage. “By tasting these grains and fruits,” Angmo says, “the audience experiences the flavours of Ladakhi soil and the traditions that have sustained generations before me.”

Crucially, Stendel did not claim a singular “authentic” Ladakhi cuisine. Angmo is careful to resist that framing altogether. Her years of research hundreds of interviews across Ladakh, have taught her that food traditions are fluid, shaped by family, village, region and time. “There is no final word,” she says. “Authenticity is a loaded term.” Instead, humility, collaboration and listening guide her work. Often, the same person is a herder, fibre processor, artisan and cook, a reminder that categories imposed from outside rarely reflect lived realities.

That insistence on nuance also extends to how Ladakh is understood by the wider culinary world. Angmo is quick to challenge persistent misconceptions: Ladakh is not Himalayan but Trans-Himalayan, lying beyond the rain shadow on the Eurasian continental plate. Its terroir is fundamentally different. Ladakhi cuisine uses no masalas as commonly understood in Indian cooking, relying instead on herbs like chin-tse (Chinese celery), phololing (wild horsemint), tsa-mik (Moldavian dragonhead) and kosnyot (wild caraway). Staples like momo are Tibetan in origin, not Ladakhi, and thukpa is not a single noodle soup but a category of over 35 dishes, many without noodles at all. Baking traditions rooted in barley, buckwheat, millet and wheat further distinguish Ladakh’s food culture from both tandoor-based and deep-fried subcontinental cuisines.

What ties these culinary narratives back to the festival’s broader vision is the attention to systems, not just outputs. As Bidisha Dey notes, Journeying Across The Himalayas is an extension of Royal Enfield’s long-term commitment to the region, partnering with over 100 Himalayan communities to build adaptive capacity in the face of climate change, while encouraging mindful travel through the philosophy of Leave Every Place Better. The festival brings together the Social Mission’s seven pillars from craft conservation and living heritage to youth fellowships, biodiversity and road safety into a single, living platform.

Angmo’s work mirrors this long-view approach. Through Ladags Earth Agro Foods, she produces limited, seasonal, producer-led confections that honour ecological balance. She avoids sea buckthorn despite living amid it, recognising its role as winter sustenance for birds. Apricots are preserved to prevent waste in a region where over half the harvest is lost annually. New initiatives, like high-altitude beekeeping on alfalfa farms, are introduced cautiously, tested rigorously, and never scaled beyond what the land can sustain. “We take from the land only what we cultivate responsibly,” she says. The contemporary consumer, she believes, understands this restraint.

In many ways, Journeying Across The Himalayas succeeded because it resisted spectacle in favour of substance. Whether through food, craft, music or dialogue, the festival demonstrated that cultural preservation is not about freezing traditions in time, but about allowing them to speak, on their own terms, in their own voices. From hearth to table, from landscape to plate, the stories of the Himalayas were not performed. They were lived, shared, and understood.

And perhaps that is the most lasting takeaway of Ours to Tell: that the future of cultural storytelling lies not in who is listening the loudest, but in who is finally being heard.

December 21, 2025, 17:24 IST