China claims the vast majority of the South China Sea and, in recent months, has ramped up efforts to prevent the Philippines from providing supplies to personnel aboard the Sierra Madre. Analysis of ship-tracking data and videos over the past year shows that Chinese coast guard and militia ships have repeatedly swarmed and collided with Philippine resupply vessels. The Chinese vessels have also increasingly deployed water cannons at close-range, at times disabling Philippine ships and injuring sailors.

Any further escalation, warn Western and Philippine officials, could lead to open conflict.

Biden administration officials have stressed that an armed attack on a Philippine military vessel, such as the Sierra Madre, would trigger a U.S. military response under a 1951 mutual defense treaty. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said after meeting with President Biden in Washington earlier this month that the killing of Philippine service members by a foreign power would also be grounds to invoke the treaty.

China has spent the past three decades expanding its presence in the South China Sea, a strategic waterway through which a third of global shipping passes, according to the United Nations. Beijing may not intend to start a war here, analysts say, but repeated confrontations at sea between vessels have raised the potential for fateful accidents, also potentially provoking a U.S. response.

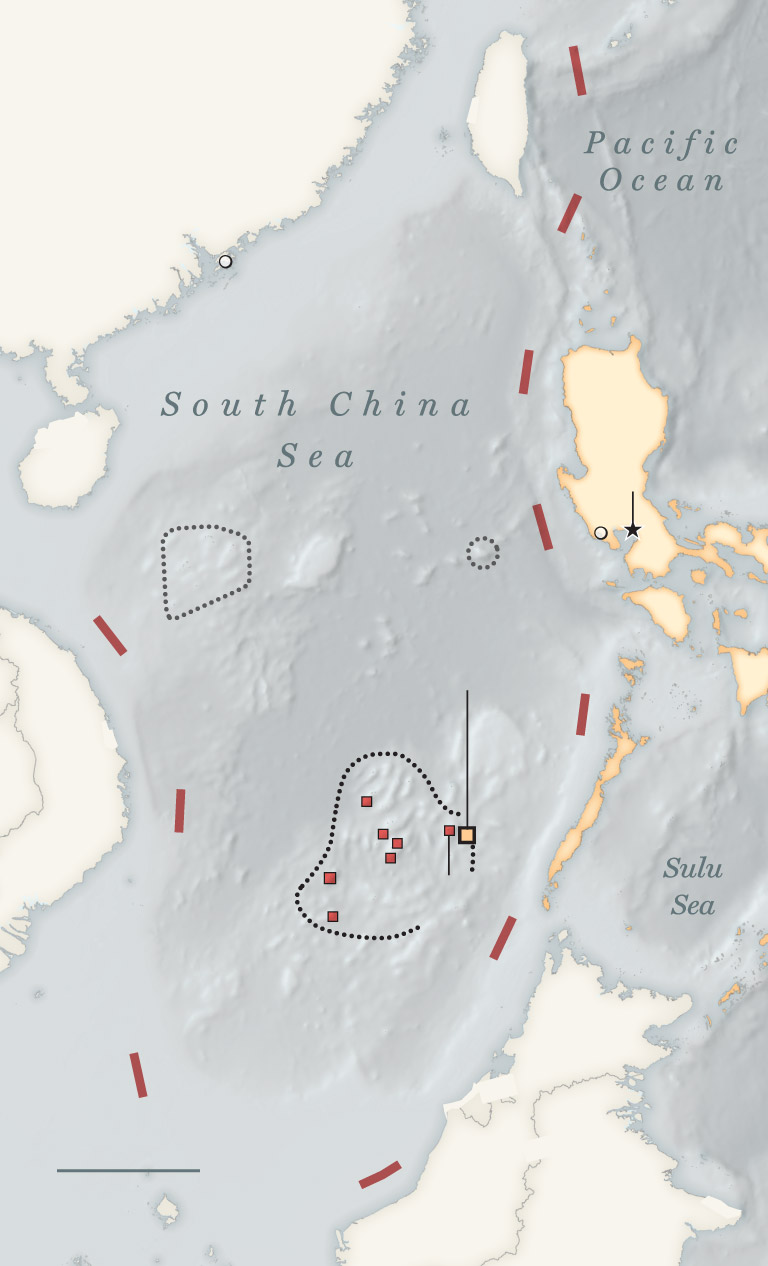

10-dash line

China’s maritime claims

Seven islands

occupied by China

within the

Spratly Island

chain

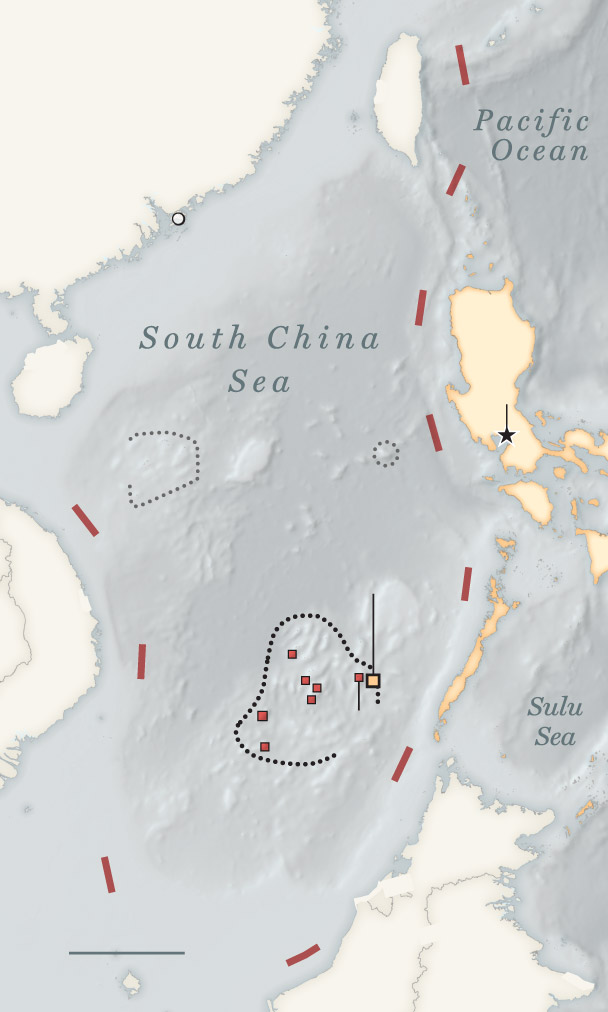

China’s maritime claims

Seven islands

occupied by

China within the

Spratly Island

chain

China’s maritime claims

Seven islands

occupied by

China within the

Spratly Island

chain

Adding to the uncertainty is the question of what to do with the 328-foot Sierra Madre, which is no longer seaworthy and badly degraded after decades of exposure to the elements. The Chinese say replacing the ship with a more permanent structure is unacceptable. But in interviews, top Philippine officials said emphatically they will not give up control of Second Thomas Shoal.

At no time in recent decades have geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea reached such a prolonged and precarious state as they have recently at Second Thomas Shoal, said Harrison Prétat, deputy director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) at the D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The dispute over that shoal — one of dozens of contested islands, reefs and other features — is part of an increasingly perilous competition among the countries that border the South China Sea for sovereignty over these strategic waters and control of the energy and other resources that lie below.

As China under leader Xi Jinping has grown ever more aggressive in pursuing its claims, Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia have been taking steps — some in public, some largely below the radar — to assert their own claims and pursue their own economic interests, potentially bringing the region closer to war than at any time in years.

Before every mission to resupply the Sierra Madre, Marcos is briefed, said Philippine officials, as is the U.S. ambassador to the Philippines, according to U.S. officials. The United States has significantly increased its deployment of Navy personnel in the Philippines in direct response to the situation at the Sierra Madre, said a U.S. State Department official. Not since the siege of Marawi in 2017, when Islamic State-affiliated rebels seized a town in the Philippine south, has the United States provided such extensive support for a Philippine military operation, said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he had not been authorized to speak publicly on the issue.

To many in the Philippines, Chinese behavior at Second Thomas Shoal, which they call Ayungin Shoal, has become a symbol of Beijing’s increasingly brazen projection of power. Orlando Mercado, a former Philippine secretary of defense, called it “the biggest, most graphic illustration of bullying.” Commodore Roy Trinidad, a spokesman for the Philippine navy, said it is a display of China’s “expansionist” ambitions.

“What’s happening in the West Philippine Sea is only a microcosm of what China wants to do to the world,” Trinidad added, using the Philippine name for the waters that it claims.

The Chinese Embassy in the Philippines declined requests for interviews and responded to questions by pointing to a previous statement saying that the Philippines has been violating China’s sovereignty. “We demand that the Philippines tow away the warship,” the statement said. Until it is removed, the statement added, China will “allow” resupply missions only if “the Philippines informs China in advance and after on-site verification is conducted.”

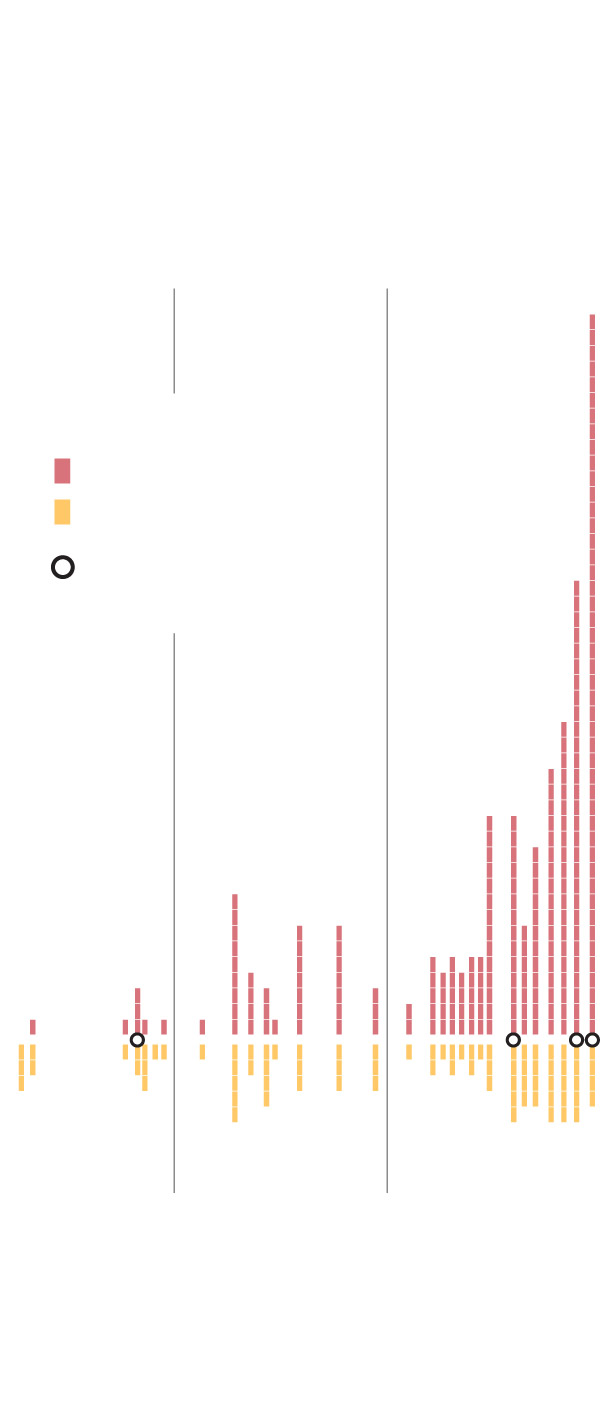

Research groups say China has hundreds of vessels deployed across the South China Sea at any time — a mix of coast guard and maritime militia, which are government-funded ships registered for commercial fishing but used to establish China’s presence in disputed waters. These vessels have loitered around the Sierra Madre for years but began to surge in number in 2023, according to ship location data tracked by AMTI. In 2021, China on average deployed only a single ship each time the Philippines conducted one of its resupply missions, which are carried out by civilian boats staffed with navy personnel. By 2023, the average had jumped to 14. During one mission last December, researchers found at least 46 Chinese ships patrolling Second Thomas Shoal.

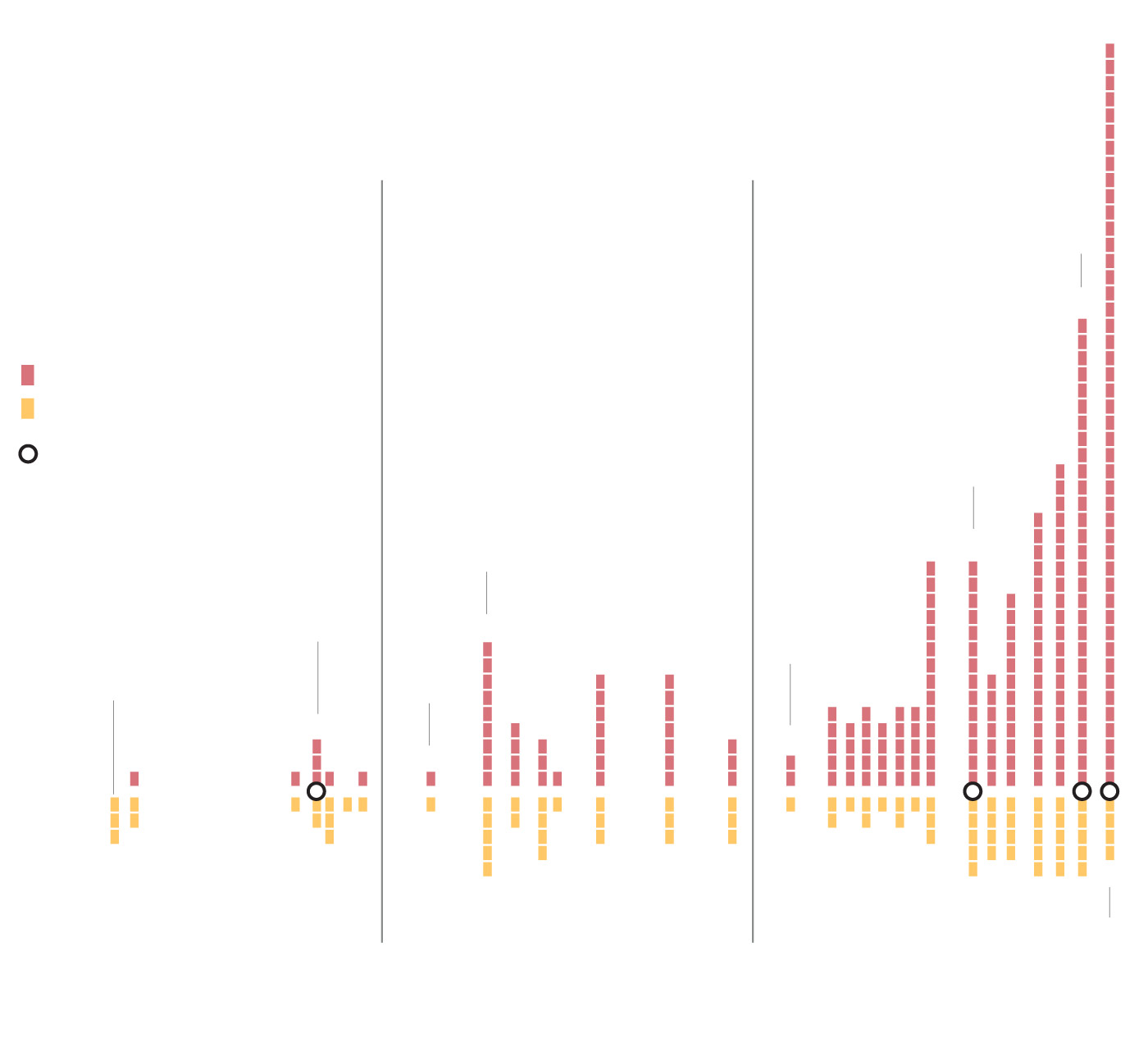

Ship traffic at Second Thomas Shoal

is on the rise during resupply runs

The Chinese response to Philippine

resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre has been to vastly outnumber the Philippine vessels.

Water cannon usage

by China*

*There have been two incidents in 2024 where China

has used water cannons on Philippine vessels:

March 5 and 23. The analysis on ships involved for

those incidents has not been completed at this time.

Source: CSIS/AMTI, Starboard Maritime Intelligence

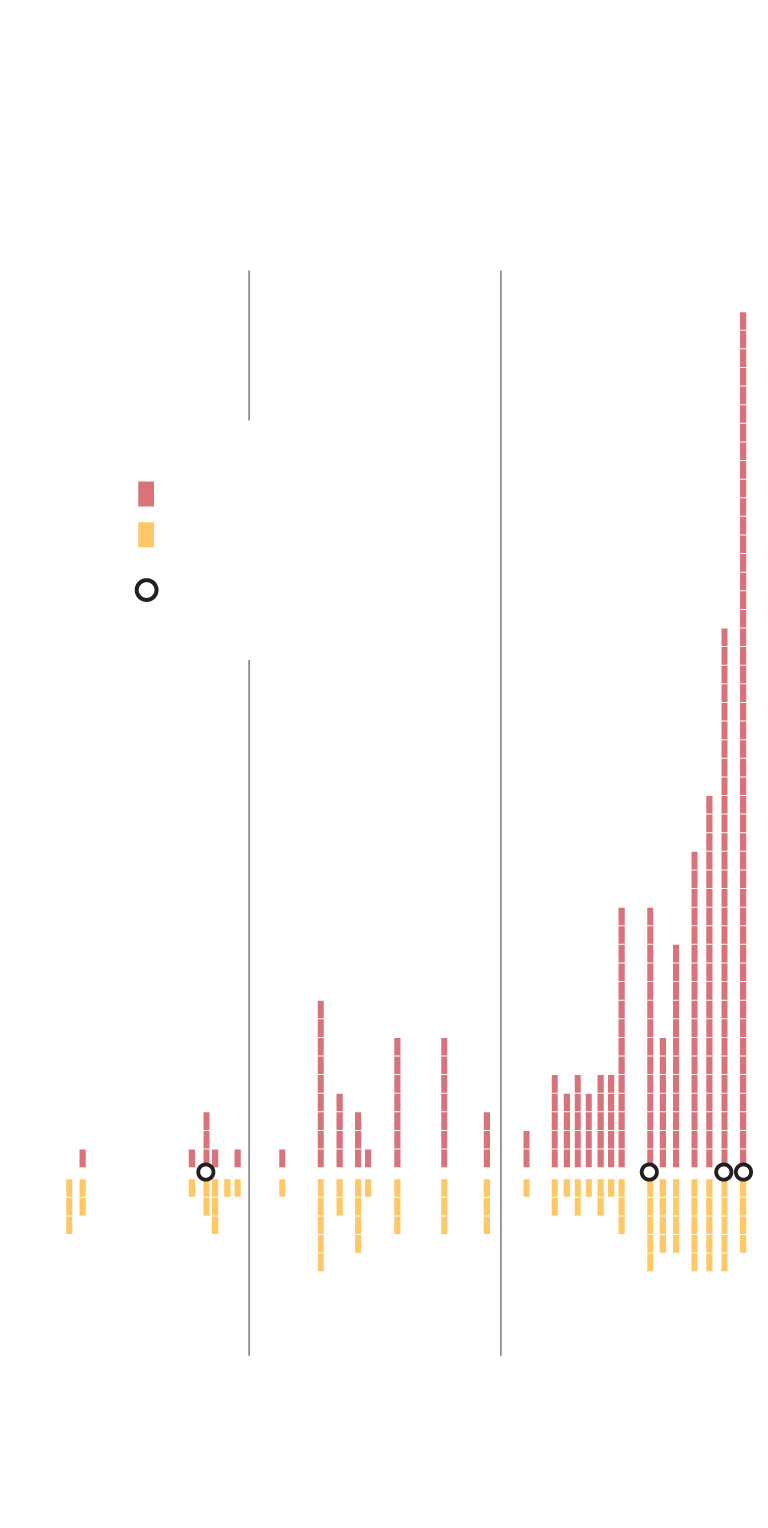

Ship traffic at Second Thomas Shoal

is on the rise during resupply runs

The Chinese response to Philippine resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre has been to

vastly outnumber the Philippine vessels.

Water cannon

usage by China*

*There have been two incidents in 2024 where China has used water

cannons on Philippine vessels: March 5 and 23. The analysis on ships

involved for those incidents has not been completed at this time.

Source: CSIS/AMTI, Starboard Maritime Intelligence

Ship traffic at Second Thomas Shoal is on the rise during resupply runs

The Chinese response to Philippine resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre

has been to vastly outnumber the Philippine vessels.

Water cannon usage

by China*

*There have been two incidents in 2024 where China has used water cannons on Philippine vessels: March 5 and 23.

The analysis on ships involved for those incidents has not been completed at this time.

Source: CSIS/AMTI, Starboard Maritime Intelligence

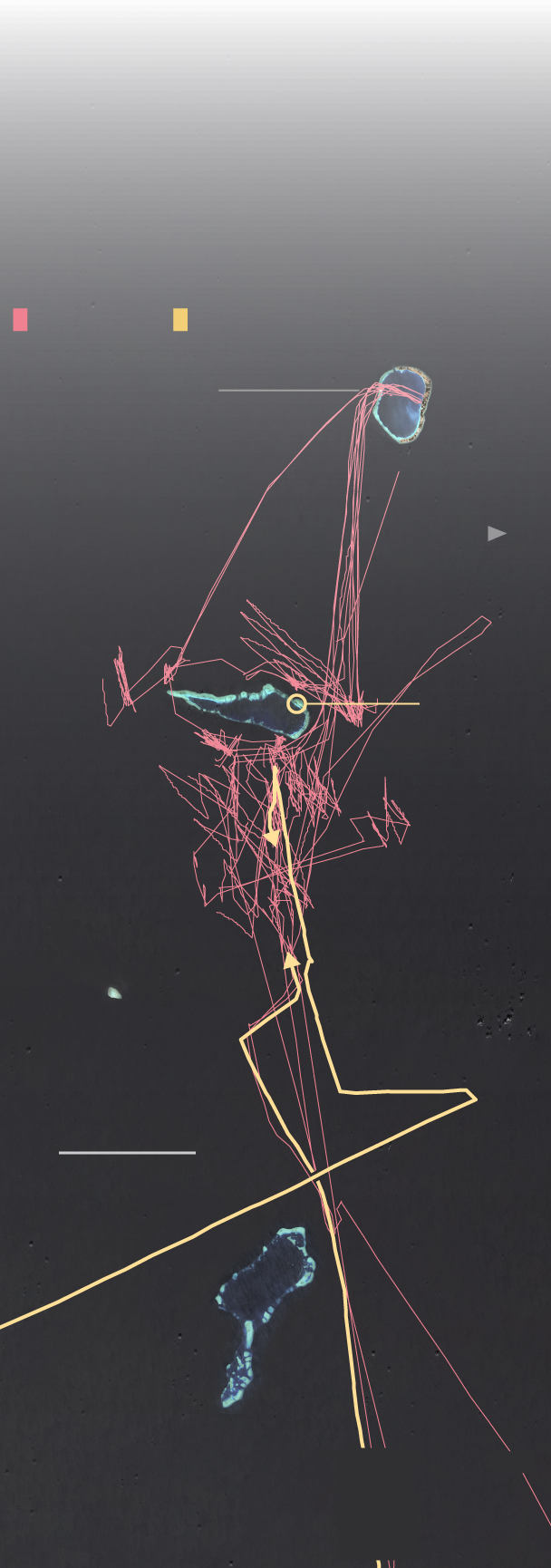

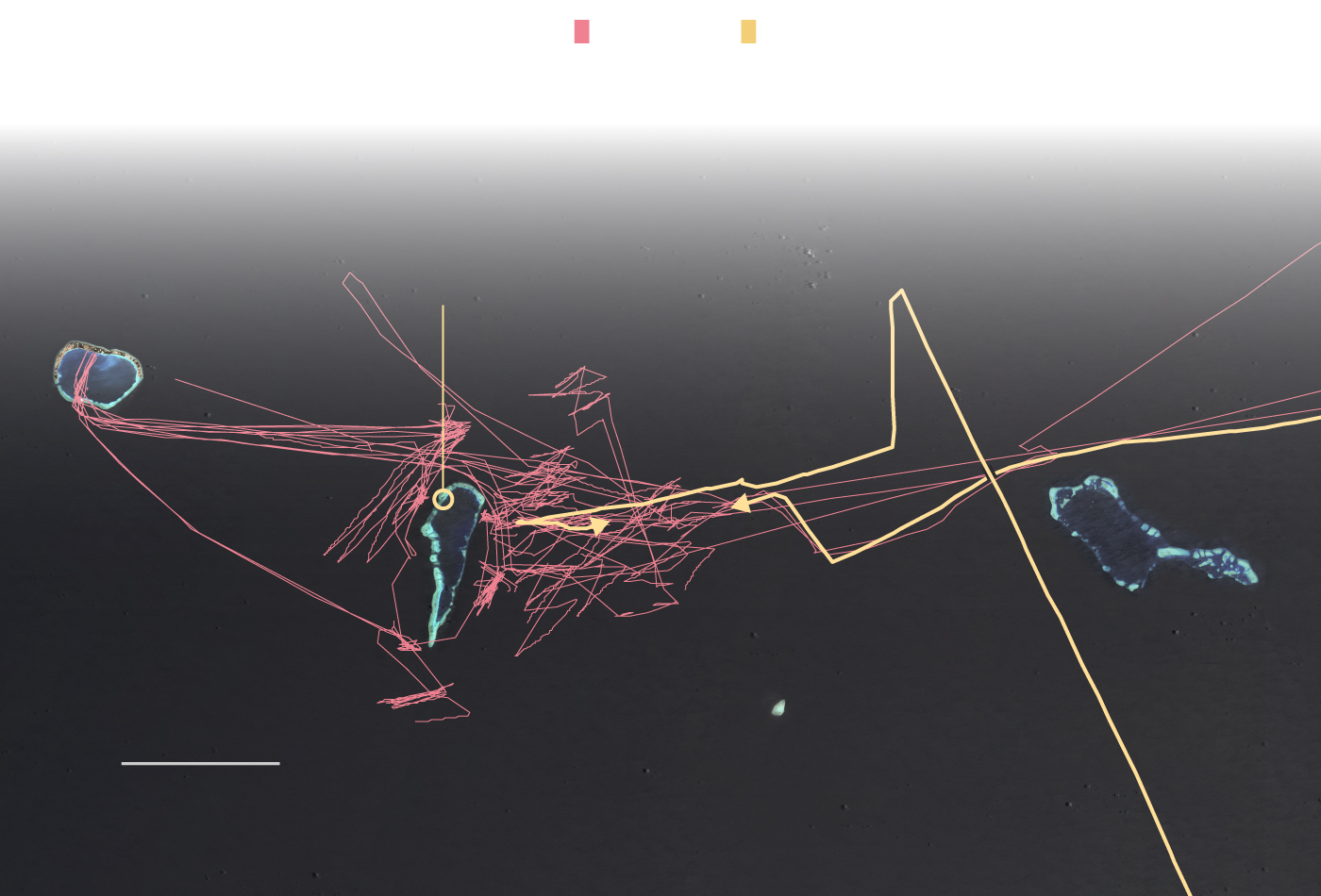

During the Dec. 10 resupply mission, Chinese ships largely based at nearby Mischief Reef tried to form a “blockade” at a greater distance from Second Thomas Shoal than before, said Ray Powell, director of SeaLight at Stanford University’s Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation. “They made the approach as tense and as difficult as possible.”

Shipping traffic on Dec. 10, 2023

China forms an overwhelming blockade

seeking to prevent Philippine ships from

entering Second Thomas Shoal. Shown

are BRP Sindigan and BRP Cabra that

were escorting two smaller ships

with supplies for the BRP Sierra Madre.

Military base

from which

China can

launch

operations.

Location

of the

SIERRA

MADRE

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off

or did not transmit location data during this incident.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for

National Security Innovation at Stanford University

Shipping traffic on Dec. 10, 2023

China forms an overwhelming blockade seeking to

prevent Philippine ships from entering Second

Thomas Shoal. Shown are BRP Sindigan and BRP

Cabra that were escorting two smaller ships

containing supplies for the BRP Sierra Madre.

Military base

from which

China can

launch

operations.

Location

of the

SIERRA

MADRE

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off

or did not transmit location data during this incident.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security

Innovation at Stanford University

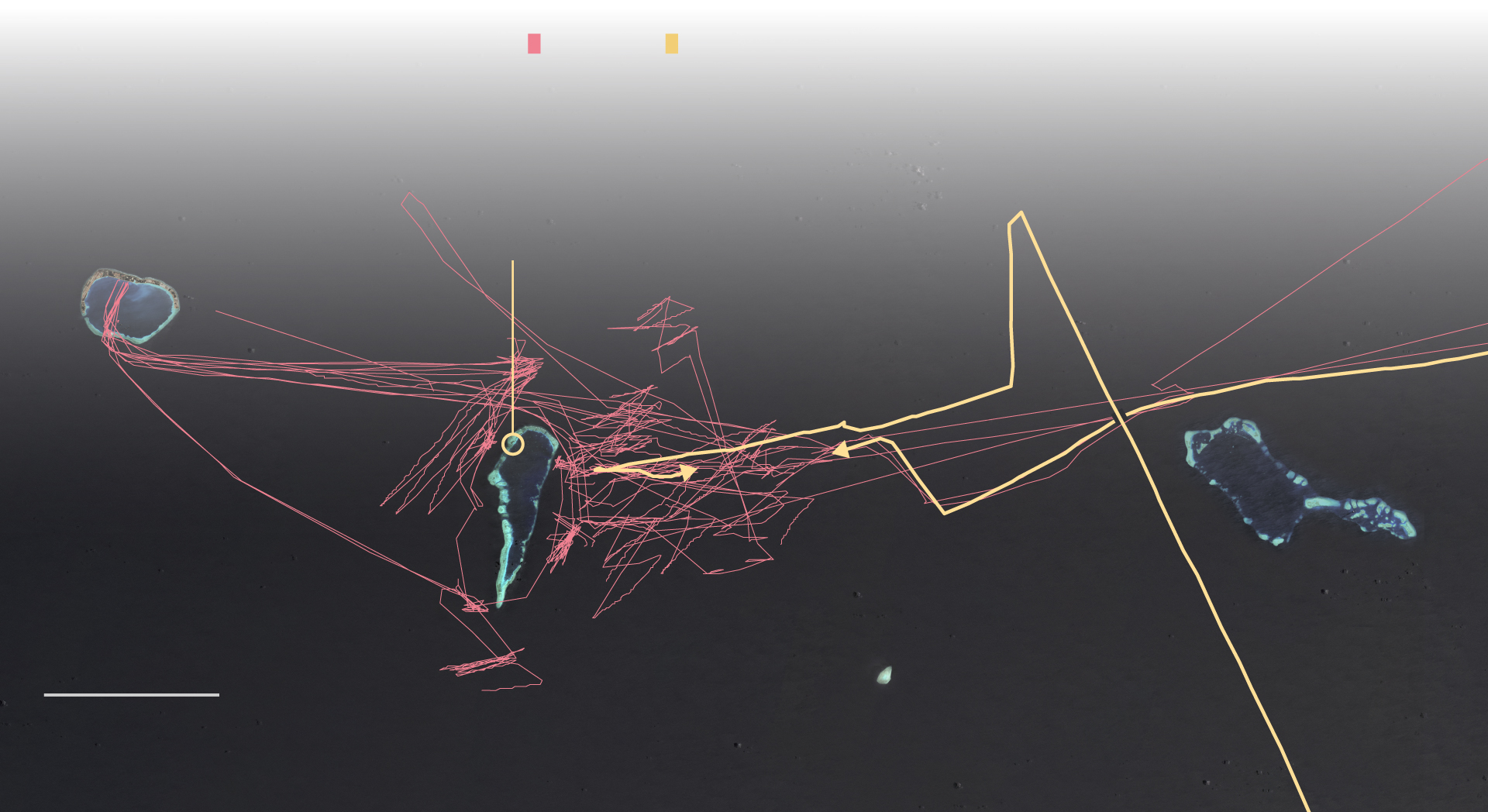

Shipping traffic on Dec. 10, 2023

China forms an overwhelming blockade seeking to prevent Philippine ships from entering Second

Thomas Shoal. Shown are BRP Sindigan and BRP Cabra that were escorting two smaller ships

containing supplies for the BRP Sierra Madre.

Location of the

SIERRA MADRE

Military base

from which

China can

launch

operations.

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off or did not transmit location data during this incident.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation at Stanford University

Shipping traffic on Dec. 10, 2023

China forms an overwhelming blockade seeking to prevent Philippine ships from entering Second Thomas Shoal.

Shown are BRP Sindigan and BRP Cabra that were escorting two smaller ships containing supplies for the BRP Sierra Madre.

Location of the

SIERRA MADRE

Military base

from which

China can

launch

operations.

Note: Some vessels had their trackers turned off or did not transmit location data during this incident.

Source: SeaLight at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation at Stanford University

Videos from that day show that as one of the four Philippine ships, M/L Kalayaan, began to near Second Thomas, two significantly larger Chinese vessels pulled up on either side of it, and one blasted it with a water cannon. The M/L Kalayaan’s engine was damaged and had to be towed back to shore, according to Philippine officials. The vessel could not reach Second Thomas, though another Philippine ship, the Unaizah May 4, made it through.

Once rare, the use of water cannons has become routine since December. During a resupply mission on March 5, two Chinese vessels deployed water cannons within several feet of the Philippine ship, shattering its windscreen and injuring four sailors on board.

The Unaizah May 4 returned to shore without delivering its cargo. When it tried again three weeks later, it was again targeted by water cannons. This time, the Chinese ships “didn’t stop until the vessel was entirely disabled,” said a Philippine military official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share undisclosed details of the incident. The water cannons caused the ship to lose propulsion and wrecked its wooden hull, forcing the crew to transport the supplies to the Sierra Madre on inflatable dinghies. When the Chinese boats came close, the official added, Chinese personnel on board also yelled at the Philippine crew. “They were shouting at us, saying, ‘Construction? Construction?’” said the official.

China has for months accused the Philippines of secretly transporting construction material to the Sierra Madre in an attempt to “permanently occupy” Second Thomas. Philippine officials deny this. Since last October, the Philippines has been conducting “superficial repairs” to the Sierra Madre to ensure habitability for soldiers, but it has not been constructing a new outpost, say officials.

With several Philippine resupply ships damaged and concerns growing over the escalating violence, Philippine officials said they have been rethinking how best to conduct the missions. “We will not be deterred,” said Trinidad, the navy spokesman. But neither, say security analysts, will the Chinese.

To map the behavior of Chinese and Philippine vessels, The Washington Post drew upon data collected by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation at Stanford University.

Both organizations track vessels based on location information transmitted by their Automated Identification System (AIS). Researchers say the data paints a representative picture of ship behavior but is incomplete because not all ships turn on their AIS. Chinese vessels, in particular, are known to turn off the AIS, or “go dark,” in the South China Sea.