The Rev. Jesse Jackson speaks during his 1984 presidential campaign in Chicago. | David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

A look back at the esteemed personalities who left us this year, who’d touched us with their innovation, creativity and humanity.

By CBSNews.com senior producer David Morgan. The Associated Press contributed to this gallery.

A protege of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and an enthralling orator, Rev. Jesse Jackson (Oct. 8, 1941-Feb. 17, 2026) was an integral part of the civil rights movement, a stirring voice for economic justice and a trailblazing presidential candidate. His runs for the White House in the 1980s, and efforts promoting voter registration, helped set the stage for another politician from Chicago, Barack Obama.

Jackson started out as a staff member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. An ordained Baptist minister, he joined the voting rights march that King led from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. King then sent Jackson to Chicago to launch Operation Breadbasket, which pressured companies to hire Black workers.

Jackson was with King on April 4, 1968, when the civil rights leader was assassinated. In 1971, Jackson broke with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and founded the civil rights organizations PUSH (later the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition) and PUSH Excel in Chicago — groups focused on education and programs designed to secure jobs for Black Americans and business for Black-owned companies. PUSH used lawsuits, and threats of boycotts, to pressure corporations to commit to diversifying their workforces.

In the 1980s, he pursued the highest political office in the nation. He told “Sunday Morning” in 1984 about the desire for common ground — what he called a rainbow vote. “There are many levels where the interests of Blacks, Hispanics, women, teenagers, peace activists, unemployed people, our interests converge, and we must always struggle, it seems to me, to move from racial battleground and polarization to economic common ground,” he said. “This is not a struggle for Blacks only. The industrial collapse of auto, steel, electronics, rubber and textile was not Blacks only. The need for a new fuel policy is not for Blacks only. This cry for health and education to be served based upon need, not just based upon wealth, is not Blacks only. So, I think that the coalition is being underestimated.”

And even before he entered the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination process, Jackson saw beyond the immediacy of a run for the Oval Office: “The energy that we’re organizing now is not just focused on the White House,” he said. “It’s focused on every level of government. We’ll be able to translate the energy of this national enthusiasm into higher voter registration, more participation, more coalition. We’re not talking about just a person running; we’re talking about many people running for Congress and state legislature and supervisor and sheriff and registrar and tax assessor and school board. We’re not talking about a kind of one-horse race.”

He achieved a few Democratic primary wins during his 1984 run — the first African American candidate to do so. Jackson’s statements in support of the Palestinian Liberation Organization drew critics, while his challenging of establishment Democrats was also met with resistance. But in 1988, when Jackson mounted another run, almost 7 million Democratic voters picked him in the primaries and caucuses. He won 12 states, including Michigan and Virginia. (The nomination ultimately went to Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis.)

Even as his health faltered in later years, Jackson continued to speak out against racial injustice. He appeared at the 2024 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and supported a resolution backing a ceasefire in the Israeli-Hamas war.

He was also a voice in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations. “Even if we win,” he told protesters in Minneapolis during the murder trial of the officer charged in the death of George Floyd, “it’s relief, not victory. They’re still killing our people. Stop the violence, save the children. Keep hope alive.”

Robert Duvall

Robert Duvall in his Oscar-nominated performance as Lt. Col. Kilgore in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” | Zoetrope/Paramount Pictures via Getty Images

One of the best actors of his generation, Robert Duvall (Jan. 5, 1931-Feb. 15, 2026) starred in such classics as “The Godfather” and “The Godfather Part II,” “M*A*S*H,” “Apocalypse Now,” and “Tender Mercies,” for which he won the Academy Award.

In a career spanning nearly seven decades, Duvall was noted for his understated performances, subsuming himself into characters that manifested moral conflicts or ethical struggles — most notably as Tom Hagen, the Corleone family’s consigliere, in the first two “Godfather” films; Mac Sledge, a country singer seeking to redeem himself, in “Tender Mercies”; and as Boo Radley, a shy man who befriends young Scout, in the 1962 adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

But Duvall could also go large, such as his full-throttle performance as Lt. Col. Kilgore in “Apocalypse Now,” who leads a helicopter attack on a Vietnamese village in order to secure a safe zone for surfing; Bull Meechum, the overbearing Marine pilot and father in “The Great Santini”; and Frank Hackett, a corporate TV executive who runs roughshod over a news division in “Network.”

Even in small parts, he could steal a movie. In 2004, he explained to “60 Minutes” that, whether his characters were heroic or villainous, down-to-earth or tenacious, there’s a bit of Robert Duvall in all of them. “Has to be. It’s you underneath,” he said. “You interpret somebody. You try to let it come from yourself.”

The son of a Navy rear admiral, Duvall studied acting in New York alongside Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman and James Caan, and after some early TV roles, he made his film debut in “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

In “M*A*S*H,” Robert Altman’s 1970 satire of war, Duvall played Major Frank Burns, a by-the-book Army surgeon whose religious zeal didn’t get in the way of his having an affair with the hospital’s chief nurse, “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Sally Kellerman). Burns becomes a foil and butt of jokes of other doctors at the M*A*S*H unit, until he is literally driven into a straitjacket

Duvall followed with a lead role in “THX 1138,” a science fiction film directed by one of Coppola’s friends, George Lucas. But an even bigger role was Duvall’s supporting turn in Coppola’s “The Godfather.” Cast opposite Marlon Brando, James Caan and Al Pacino, Duvall played an Irish lawyer who had been “adopted” into the Corleone family — his sole client. Balancing the wishes of Brando’s Vito Corleone, the hot-headed antics of Caan’s Sonny, and the resistance of Pacino’s Michael, Tom Hagen was a tested voice of reason, a deliverer of bad news, and an instrument of revenge. He repeated the role in “The Godfather Part II.” But when Coppola went to film Part III of his gangster saga, Duvall and the studio couldn’t come to terms on salary, and so Tom Hagen was killed off.

One of his most celebrated roles was in Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now,” playing Lt. Col. Kilgore, who heads a helicopter attack on a suspected Viet Cong village, blaring Wagner on loudspeakers. Kilgore’s bare-chested speech (“I love the smell of napalm in the morning … it smells like victory”), as a forest is incinerated nearby, articulated the brutality and insanity of war, and became one of cinema’s iconic moments. Duvall took his role seriously, even as explosives were discharged all around him. “I played a guy that didn’t flinch, so I didn’t flinch. You know what I mean?” he told Esquire magazine in 2014. “I played that kind of guy — a non-flinching guy. If you flinch when the script says not to flinch, you should be fired.”

For “Tender Mercies,” playing an alcoholic country singer trying to make a spiritual and professional comeback, he sang every song himself. “They were trying to get around it,” Duvall told “Sunday Morning” in 2006, “but I said, ‘No, no. This has to be part of it. You cannot dub [another singer] later. I have to do that.'”

Duvall had said his favorite role was Gus McCrae, the Texas Ranger turned-philosopher cowboy, in the 1989 TV miniseries “Lonesome Dove.” He directed three films: “Angelo, My Love”; “The Apostle,” in which he played a Pentecostal preacher on the run from the law; and “Assassination Tango,” which was his tribute to Argentine dance.

The qualities of Duvall’s work, from the histrionic to the silent, were evident in the naturalness of his delivery. As he said to “Sunday Morning,” “What makes what I do work? It’s this, what we’re doing right now: talking and listening. … That’s the beginning and the end. The beginning and the end is to be simple.”

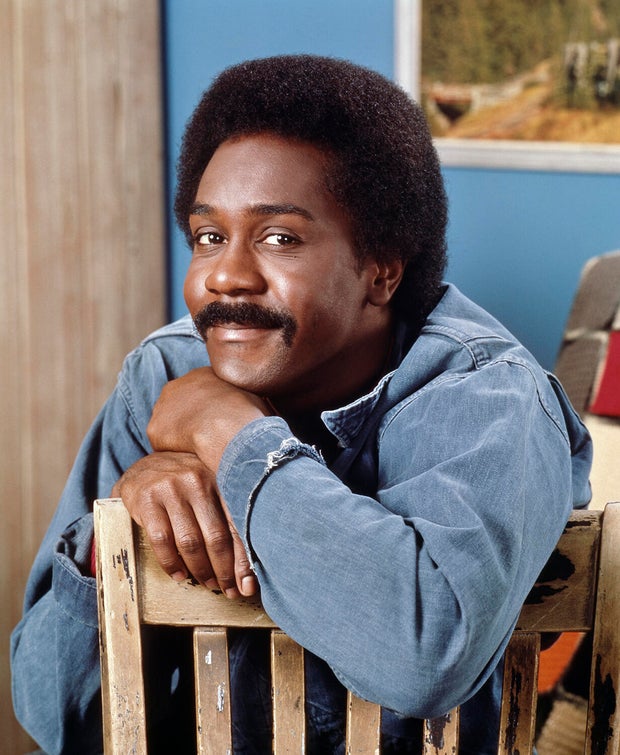

Demond Wilson

Demond Wilson, star of the 1970s sitcom “Sanford and Son.” | NBCUniversal via Getty Images

Demond Wilson (Oct. 13, 1946-Jan. 30, 2026) was best known for playing Redd Foxx’s son Lamont on “Sanford and Son” in the early 1970s. Adapated by Norman Lear from the British comedy “Steptoe and Son,” about a grumpy and irascible junk man and his aspirational adult offspring, “Sanford and Son” was one of the earliest American sitcoms to feature a predominantly Black cast, and was for many years NBC’s top-rated show.

Born in Valdosta, Georgia, Wilson grew up in Harlem. As a child he appeared on radio and danced on the stage of the Apollo Theatre. As a teenager, a ruptured appendix led him to promise to devote himself to God.

He was wounded while serving with the Army in Vietnam, and upon his return to New York began acting off-Broadway, before going to Hollywood. After a guest role on Lear’s “All in the Family,” he was hired for one of the leads in “Sanford and Son.” In 2022, Wilson told the Associated Press that he was competing with Richard Pryor for the role opposite Foxx. “I said, ‘C’mon, you can’t put a comedian with a comedian. You’ve got to have a straight man,'” he said he told producers.

Debuting in 1972, the show ran on NBC for six seasons, and spent most of its run in the Nielsen Top 10 (frequently second only to Lear’s “All in the Family”). The series ended when ABC lured Foxx away to host his own variety show.

Wilson later starred in the TV shows “Baby I’m Back” and “The New Odd Couple” (playing Oscar Madison). He also appeared in “Girlfriends” and the film “The Organization.” But he did not find acting fulfilling, and in the 1980s he became an ordained minister. “Show business did not come out of me. I came out of show business,” he told Jet Magazine in 1985.

He also founded Restoration House of America, an organization that helps rehabilitate prison inmates and the formerly incarcerated, and wrote several books, including children’s stories.

Catherine O’Hara

Catherine O’Hara attends a sneak peek of “Schitt’s Creek” during the 11th Annual New York Television Festival, at SVA Theatre, October 22, 2015 in New York City. | Matthew Eisman/WireImage

Emmy-winning actress Catherine O’Hara (March 4, 1954-Jan. 30, 2026) was best-known for her roles on the sketch comedy series “SCTV,” “Schitt’s Creek,” and the films “Home Alone” and “Beetlejuice.”

Born in Toronto, O’Hara grew up in a family that encouraged being funny, she told The New York Times in 2016: “My dad would tell jokes, and my mom would tell stories and imitate everyone within the stories. I think everyone is born with humor, but your life can beat it out of you, sadly, or you can be lucky enough to grow up in it.”

A member of the Second City improv troupe, where she originally understudied for Gilda Radner, O’Hara helped create the Canadian series “SCTV,” for which she played a multitude of characters alongside cast members John Candy, Joe Flaherty, Eugene Levy, Andrea Martin, Dave Thomas and Harold Ramis. O’Hara dropped out of the cast for its third season, but rejoined after the show moved from syndication to NBC and then Cinemax. She won an Emmy as a co-writer.

Among her movie roles, O’Hara played quirky supporting characters in Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours” and Tim Burton’s “Beetlejuice,” and was also featured in “Dick Tracy,” “The Paper,” “Wyatt Earp,” and “Orange County.” But her most recognized role was as Macaulay Culkin’s mother in “Home Alone.” She was also part of Christopher Guest’s ensemble in his improvisational mockumentaries, including “Waiting for Guffman,” “Best in Show,” “A Mighty Wind,” and “For Your Consideration.”

Her biggest splash was as flamboyant matriarch Moira Rose in “Schitt’s Creek.” The show, created by her “SCTV” costar Eugene Levy and his son Dan, centers on a wealthy family losing all their money and being forced to live in a motel in a small town.

In 2016 O’Hara told “CBS This Morning” she had some initial reservations about doing the series. “You never know how long it’d go, and to lock into one character, that’s kind of scary,” she said.

“Schitt’s Creek” ran for six years, and in its final season won nine Emmys.

In addition to winning for playing Moira Rose in “Schitt’s Creek,” she was also Emmy-nominated for “Temple Grandin,” “The Last of Us,” and “The Studio.”

O’Hara shared with The New York Times her improv secret: “My crutch was, in improvs: when in doubt, play insane. Because you didn’t have to excuse anything that came out of your mouth. It didn’t have to make sense.”

Dr. William Foege

William Foege, physician and epidemiologist, receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama at the White House, May 29, 2012. | Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Dr. William Foege (March 12, 1936-Jan. 24, 2026), a physician and epidemiologist, was a leader in the global eradication of smallpox — one of humanity’s greatest public health victories.

His interest in global health was an outgrowth from his time when, at age 15, he was stuck in a body cast for three months. “We did not have television at that time,” he said in a 2021 interview for Exemplars in Global Health. “So, I was forced to read, and came across Albert Schweitzer, and became interested in Africa, and in medicine.”

Following medical school, and years before he served as director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Foege was a member of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service, as well as the Peace Corps, and studied at Harvard School of Public Health, where his interest in smallpox took hold.

Smallpox vaccination campaigns were well established by that time. In fact, the disease was no longer seen in the U.S. But infections still occurred elsewhere.

As a medical missionary in Nigeria in the 1960s, Foege and his colleagues developed a “ring containment” strategy, in which a smallpox outbreak was contained by identifying each smallpox case and vaccinating everyone with whom the patients might come into contact. The method relied heavily on quick detective work and was born out of necessity; there simply wasn’t enough vaccine available to immunize everyone, Foege wrote in his 2011 book “House on Fire.”

It worked, and was instrumental in ending the spread of the disease. The last naturally-occurring case of smallpox was spotted in Somalia in 1977. Three years later, the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated for good.

From 1977 to 1983, Foege was director of the CDC. He was later executive director at The Carter Center, and senior fellow at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2012, he received the Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama. He was called “the Father of Global Health” by Duke University President Richard Brodhead.

Foege said in the 2021 interview that he advises students to think about editing their own obituary every day:

“‘You won’t realize it, but if you wake up in the morning knowing that you’re going to edit your obituary, it makes a difference what you will try to do that day.’ Is there a unifying field theory in all this? Yes. We belong to a group of optimists who believe that we can change the future. So, you wake up every morning knowing that you’re changing the future.”

“Uncle Floyd” Vivino

“Uncle Floyd” (Floyd Vivino) photographed in New Jersey in 1984. | MPIRock/MediaPunch via Getty Images

Beginning in the mid-1970s, “The Uncle Floyd Show” was a low-rent affair, broadcast from a UHF station whose studios were housed in an actual house in West Orange, New Jersey. Hosted by comedian and piano player Floyd Vivino (Oct. 19, 1951- Jan. 22, 2026), with a puppet named Oogie and a menagerie of vaudevillian sidekicks, the series — filled with corny jokes and skits, honky-tonk piano, musical acts, and letters from viewers — was ostensibly a children’s variety show, but it played more as a parody of kids show hosts like Soupy Sales (and presaged later ironic kids shows like “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse”).

“We produced the shows without a script and never a rehearsal,” he told NJ Arts in 2024.

The show appealed to older kids and to punk artists (Cyndi Lauper, Bon Jovi and The Ramones were musical guests). When David Bowie met Vivino backstage at a New York appearance, he told him he’d learned of “The Uncle Floyd Show” from John Lennon. Bowie even name-checked Uncle Floyd in his song “Slip Away.”

“The Uncle Floyd Show” developed a cult following. A broadcast window on NBC’s late-night schedule in the early ’80s, airing after David Letterman, was short-lived, and the show returned to cable until 2001.

Vivino, who hailed from a theatrical family and attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, wore his love for all things New Jersey on his sleeve. (His anthem was “Deep in the Heart of Jersey.”) In addition to his live revue shows and charity events, he hosted radio broadcasts and podcasts, and made a few film appearances, including playing an Armed Forces Radio DJ opposite Robin Williams in “Good Morning, Vietnam.”

In a 2011 newspaper interview, Vivino described giving a performance while a high school student in Glen Rock, N.J. in 1968: “The orchestra was playing ‘Everything Is Coming Up Roses’ and I felt the rush of 600 people clapping for me. It was then and there that I knew I was going to be an entertainer. I did not belong on the basketball court or in the science lab.”

Valentino

Valentino, pictured in Rome with his models in an undated photo. | Pascal CHEVALLIER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

The designs of Valentino Garavani (May 11, 1932-Jan. 19, 2026) were fashion-show staples for nearly half a century. Known by his first name, Valentino clothed royals, first ladies and movie stars, from Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Princess Diana and Queen Rania of Jordan, to Julia Roberts and Cate Blanchett.

Born into an affluent family in the northern Italian town of Voghera, his love of movies — and movie stars — lead him to fashion. He studied in Milan and Paris, and worked for designers Jean Desses and Guy Laroche, before launching his own firm in Rome in 1959.

“Why I ever thought I could go out on my own like that, God only knows,” Valentino told The New Yorker in 2005. “But my parents gave me a little money and I started. I had no idea what I was getting into. Sometimes ignorance is a wonderful thing.”

Besides his trademark shade of red, Valentino’s recognized flourishes included bows, ruffles, lace and embroidery.

Valentino’s firm would expand to include ready-to-wear, menswear and accessories. In 1998, he and his partner, Giancarlo Giammetti, sold the label to an Italian holding company for an estimated $300 million, with Valentino remaining in a design role until 2008.

In a 2016 interview with The Talks, Valentino said beauty was the most important thing to him: “Since I was a child I loved the way a dress looks, I admired a great face, a lovely body. I enjoy the beauty in a woman, in a man, in a child, in a painting. Beautiful things are important and make life important. Since I was a kid, I’ve been encouraging myself to appreciate beauty.”

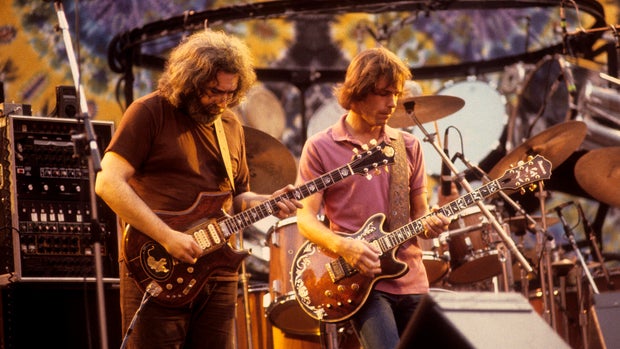

Bob Weir

Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir perform with the Grateful Dead at the Greek Theater in Berkeley, Calif., Sept. 13, 1981. | Clayton Call/Redferns via Getty Images

In 1963, Jerry Garcia met singer and musician Bob Weir (Oct. 16, 1947-Jan. 10, 2026) in a Palo Alto, California, music shop. Weir was 16, struggling in school but showing promise on the guitar. With drummer Bill Kreutzmann, bassist Phil Lesh and keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, they soon founded what became one of the world’s most beloved bands, creating improvisational jams of blues, jazz, folk, country and psychedelia.

The Grateful Dead grew into a touring powerhouse, playing for an army of loyal fans as they built a presence spreading from the San Francisco Bay Area. Over three decades they only had one Top 10 hit (1987’s “Touch of Grey”), but at their peak, they took in $50 million or more a year from live shows. In the days before social media and viral marketing, “Deadheads” were encouraged to record concerts and trade tapes, creating an archive of performance art unparalleled in the music industry.

“Longevity was never a major concern of ours,” Weir said during the 2025 Grammys, when the Dead received the MusiCares Persons of the Year honor. “Spreading joy through the music was all we ever really had in mind, and we got plenty of that done.”

It looked like the “long, strange trip” would end when Garcia died in 1995 at the age of 53. But the Dead continued — and Weir was instrumental in keeping the sound of San Francisco’s counterculture alive. The remaining band members played together and, in collaboration with guitarist John Mayer, also toured as Dead & Company. Weir also released live albums with Wolf Bros., and even performed Dead music with symphony orchestras — truly classic rock. Weir also founded the Tamalpais Research Institute, a high-tech studio for streaming live audio and video on the internet.

In 2024 the Grateful Dead were named Kennedy Center Honorees.

“A song is a living critter,” Weir told “Sunday Morning” in 2022. “If I may wax hippie metaphysical for you, the characters in those songs are real. They live in some other world, and they come and visit us through the musicians, through the artists who have dedicated their lives to being that medium and inviting those critters from other worlds to come and visit our world and entertain the folks, because that’s all they want to do. It’s they just want to meet us and we meet them, and that’s what we do.”